This article presents the Alpha development stage Power Subsystem design with some notes touching on refinements to be completed in later stages. A light-weight requirements discussion is included to ground the design, and the (design assumption) Kobalt 80V battery ecosystem is introduced. The Power Subsystem design is split into backend and frontend components with an intervening Intermediate Voltage (IV) designed to abstract the backend and provide more flexibility and a rough order of magnitude (ROM) power budget is included. Runtimes and relative burden on key components are estimated. An initial DIN rail layout is presented to secure components.

Introduction

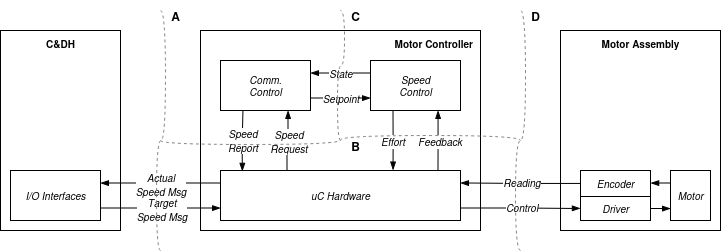

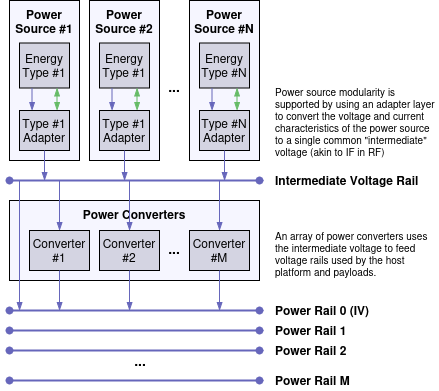

As introduced in the top-level design article, The Power Subsystem is arranged around abstraction of a power “backend” with energy sources such as batteries from a power “frontend” with voltage rails:

This subsystem provides power to the entire platform by abstracting the backend with an Intermediate Voltage (IV) rail that then feeds frontend power rails. While this design introduces additional conversion inefficiencies, it allows for greater flexibility in powering payloads such as sensors and upgrading individual components.

GARP Article Series

The Ground Autonomy Research Platform (GARP) is a home-grown UGV designed and built to support independent learning of robotics and autonomy through a full stack from hardware to behavioral autonomy and HMI. To document the implementation of GARP, I’m capturing the process in a series of articles that I’ll link here as they’re completed:

GARP Article Map

- Motivations and Design of a UGV for Robotics Research

- GARP Power Subsystem

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

- GARP Mobility Subsystem

- Motor Selection

- Subsystem Design

- Motor Controller

- C&DH

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

- GARP E-Stop

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

Requirements

The GARP’s Power Subsystem serves a key role in providing reliable, extensible, and scalable power to the rest of the platform. This introduces several requirements, some of which are direct, as in providing regulated voltages, whereas others are indirect, like not electrocuting anyone. The direct requirements are mentioned here in (roughly) decreasing order of importance.

Electrical Safety

The GARP involves voltages and currents that are potentially unsafe and could cause serious harm.

Furthermore, much of the work reported in the early stages of GARP development is “fast and loose” and should not be done by anyone.

Do not try this at home.

Starting with one of the most important requirements, the subsystem must provide layered protection that protects the battery from over-draw and back-powering. As discussed in the next section, the batteries to be used include a battery management system (BMS) with some protection electronics, but additional layers should be introduced in the integrated assembly to provide redundancy. In addition to protecting the batteries, the backend converters should be protected from overcurrent conditions as they will be handling significant amounts of power. The other major threat in this system is from voltage spikes from motor stopping. While the motors do not publish statistics on their back EMF, &c., this factor should at least be considered and sanity-checked and measuring these values once the motors have been proven out is also an option.

Second to system backend safety, the frontend must provide regulated power to platform components and can provide another layer of safety by incorporating their own overvoltage and overcurrent protections.

The final key requirement is reporting of status of the Power Subsystem. Ideally voltages and current across most lines would be metered in real time, but the high voltages and currents make most common existing breakouts infeasible for the GARP (at least on the backend.) The batteries themselves do include very low resolution reporting of charge level.

A nice-to-have is the ability to hot-swap batteries. This is notionally feasible given the current top-level subsystem design where multiple power sources contribute to a single IV interface, but in practice this introduces significant complexity beyond simple passive combining approaches.

Finally capacity is important as it will determine run-time given a GARP loadout, but as one of the design assumptions is using the Kobalt 80V battery series I already possess, this factor is more a matter of tracking available capacities and understanding trades. Fortunately this battery series offers significant capacity.

Kobalt 80V Battery Ecosystem

The Lowe’s store brand Kobalt offered a series of cordless lawn tools powered by 80V Lithium Ion batteries. Despite numerous reports of Lowe’s discontinuing the line, these tools and their batteries are still available for purchase. Most importantly for the GARP Power Subsystem design, I own a collection of batteries and chargers from this line and would like to use them to power the GARP.

While I haven’t done much to characterize these packs yet, and there isn’t much data available online, here are a few of the salient factors for the two variants of pack I plan to use to power the GARP:

Kobalt KB 280-06

- 11.7 x 8.26 x 16.8 cm (1632 cm3)

- 1485 g

- 144 Wh / 2.0 Ah

Kobalt KB 480-06

- 11.7 x 8.26 x 16.8 cm (1632 cm3)

- 1990 g

- 288 Wh / 4.0 Ah

Electrical Safety

The GARP involves voltages and currents that are potentially unsafe and could cause serious harm.

Furthermore, much of the work reported in the early stages of GARP development is “fast and loose” and should not be done by anyone.

Do not try this at home.

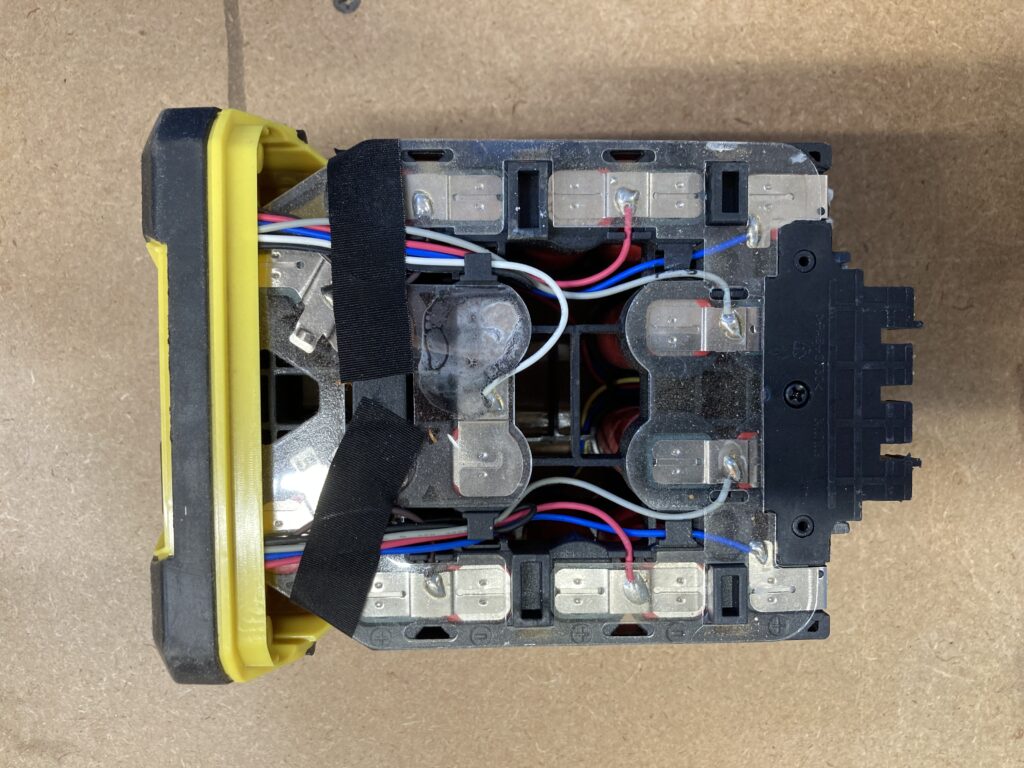

Internally, the packs are composed of twenty 18650 cells in series. This arrangement would be expected to yield ~84 V when fully charged and ~50 V when fully discharged. Embossing on the cells appears to indicate these are Sanyo UR18650RX cells with a nominal voltage of 3.6 V, discharged voltage of 2.75 V, a maximum 20 A discharge current, and a 1950 mAh capacity. Anecdotally, the batteries tend to leave the OEM chargers at ~82 V and cut out at ~55 V, which generally agrees with the values from the datasheet. The primary exception is the marked pack capacity of 144 Wh, which would be expected to be 156 Wh from the cell arrangement. I also expect that there is some protection circuitry in the packs to prevent current over draw situations, but this design will not depend on those features being present.

The packs expose four terminals on the back side marked (-), (Ω), (C), and (+), interposed with three alignment slots:

Unsurprisingly, when measured the (-) and (+) are the DC voltage terminals for the pack. The (Ω) and (C) are a little less clear, although I expect them to be a thermistor contact and (common) ground for measuring pack resistance. With this configuration of contacts, I’m expecting the DC voltage levels (with a capacity curve) will provide estimates of pack charge levels and the thermistor resistance will provide pack temperature for safety cutoff. These contacts will need to be exposed when integrated with the GARP, and further evaluated when Power Subsystem monitoring is introduced. As a data point, for a pack showing one of three charge indicator LEDs, the voltage across the (-) and (+) terminals is 71.89 V, and the resistance from the (-) terminal to (Ω) is 93.92 kΩ- all other combinations are open or 0 Ω.

Given the stated 144 and 288 Wh capacities, and assuming a maximum discharge rate of 20 A, each pack would yield 5 and 10 minutes of run time, respectively. That said, the full 20 A draw would be 1600 W of power- to refine this, consider a strawman power budget:

| Consumer | Nominal Operation | High Power |

| Motors | 100 W | 200 W |

| C&DH | 5 W | 10 W |

| Navigation Computer | 25 W | 50 W |

| Perception Computer | 50 W | 100 W |

| Subtotal | 180 W | 360 W |

| Conversion Losses | 20% | 20% |

| Total | 216 W | 432 W |

| Current at 75 V (% of 20 A) | 2.9 A (14%) | 5.8 A (29%) |

| Runtime (144/288/576 Wh) | 40 m/80 m/160 m | 20 m/40 m/80 m |

This indicates that if running two concurrent batteries, the system would run at roughly 7%/15% of max current capacity, and that runtime would range from 40-160 minutes in nominal operation or 20-80 minutes in high power operation, depending on the packs’ capacities.

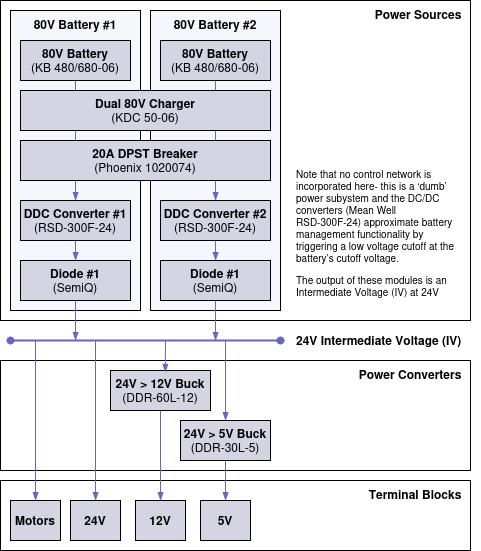

Power Subsystem Backend

To meet the above requirements, consider the following candidate design:

Kobalt 80V Dual Charger (KDC 50-06)

The Kobalt 80V Dual Charger provides the primary external interface to batteries for GARP: It provides physical fixture of the batteries while also breaking out their terminals.

There is little technical documentation on the dual charger available, so the safety features present will require investigation of the device, but it can be expected to allow duplicating the terminal leads internally which can then be routed externally and to connection to the GARP. In addition to providing the physical fixturing of the batteries, the charger also provides the GARP with a built-in battery charger by plugging the charger into a standard AC outlet. It is unclear if it will be possible to run the GARP from this charger while plugged into the wall, and if batteries will need to be present to draw power from this device, but they key features are reasonably low-risk: breaking out battery terminals, and providing physical fixture of the batteries. As discussed in the battery section, the battery terminal breakouts will provide an 80 VDC pair, and the thermistor (Ω) and common (C) outputs.

DPST Breaker (Phoenix Contact TMC 72C 20A)

The Phoenix Contact 72C 20A Dual-Pole Single-Throw (DPST) breaker will serve as the primary internal power switch for the GARP while also (notionally) providing an initial layer of current draw protection for the batteries. The breaker will accept current drawn from the battery terminal breakouts retrofit into the Dual Charger and provide switched power to the power converters producing the Intermediate Voltage (IV).

From trip curves on the OEM datasheet, the breakers will trip in under a second at ~126 A. As this is primarily useful as a switch and would not adequately protect the batteries from overcurrent draw, I expect to install fuses in series with the breaker. An alternative would be to install a lower rated breaker, but this would prevent use of the batteries at their full 20A current capacity. A simple fuse panel or drawer-type fuse will be used. Furthermore, for the Beta and/or v1.0 stages, this breaker may be supplemented with another switch that can be controlled externally to the GARP.

The breaker outputs 80 V from the batteries for consumption by the backend DDC power converters that produce the IV.

DDC Converters (Mean Well RSD-300F-24)

The DC-DC Converters (DDCs) take 80 V from the batteries (having been mediated by the breaker) and down-convert it to 24 V for the IV. They should also provide adequate regulation of the output power and provide some amount of transient protection.

The Mean Well RSD-300 series are a line of railway grade DDCs with a 300 W power rating and a number of different input and output voltage ranges. From the datasheet, the “F” indicates an input voltage range of 50.4 to 93.6 VDC which adequately covers the output voltage range of the batteries. The “-24” indicates a 24 VDC output and a current rating of 12.5 A. This will limit the output of the batteries and so if the GARP ends up needed more power, later stages may either replace these converters. The dominant loads on the IV will be up to 100 W from the motors and 60 and 30 W from the frontend 12 V and 5 V buck converters (respectively). During development the motor loads will be the first to stress test the DDCs, followed by the navigation and perception computers which will be fed by the frontend buck converters. This will provide a staged “smoke testing” during development.

The DDC’s efficiency is above 90% for loads over ~75W but is less efficient in the upper range of battery voltage and for smaller loads. That said, outside of initial development in the Alpha stage, the strawman power budget indicates that loads are expected to reach ~200-300W for operation with a single battery or ~100-150W for two batteries which puts the DDC in the 30-50% load range.

The RSD-300 includes overload protections that limits output current, and a 4 kVDC input/output isolation to help prevent motor transients from damaging the batteries. There is some inrush compensation, but it is still rated at 45 A which could be too great for the batteries to supply. If this becomes an issue and a suitable DDC replacement is not available, either a component to delay initial current draws with be introduced, and/or power consumer start-ups will be staggered.

Diodes (SemiQ SBD Parallel Power Module)

The paired diodes on the outputs of the DDCs serve to prevent back-powering one DDC by another. This is necessary as the Mean Well RSD-300s do not have a parallel feature (this feature is forgone given the significant cost increase of designs with these features.)

From the datasheet, the diodes have a 600 V reverse voltage and are rated above 20 A even for high temperature operation. The forward voltage drop ranges from 1.5-2.8 V, which given that the selected DDCs do not have a tunable output voltage means the voltage on the IV will actually be roughly 21.2-22.5 V. (The motors and frontend will need to be able to operate with this range of input voltages.) The diodes are mounted onto a tandem package that will be convenient for installation on the DIN rail with a significant heat sink, but temperature derating will need to be monitored during the Beta stage.

The diodes output power to create the 24 V IV, the interface between the Power Subsystem backend and frontend.

Power Subsystem Frontend

12V and 5V Buck Converters (Mean Well DDR-60/30L-12/5)

The Mean Well 12V and 5V buck converters are the primary constituents of the Power Subsystem front end and provide the voltage rails the bulk of the compute and payload systems will use. Their datasheets are available here:

The “L” variant provides for the greatest input voltage range providing some flexibility should the IV need to be changed to (e.g.) 48 V. The efficiency of both converters is roughly 90%, which with the efficiency of the DDCs generally aligns with the strawman power budget’s losses. The buck converters’ outputs are tunable, and so can be dialed in. The frontend converters have similar protection features to the backend DDCs including overload and 4 kVDC input/output isolation.

Terminal Blocks

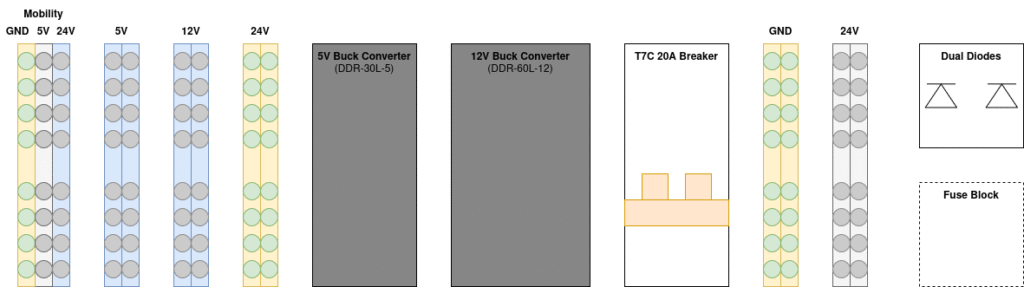

The draft terminal layout on the Power Subsystem DIN rail is depicted below:

This aims to move the switch towards the center of the rail while minimizing the routing of wiring lateral across the chassis. The other key feature is the dedicated mobility terminals at the left to localize and reserve the mobility power connections. The backend DDCs will be mounted to DIN rails on the sides of the chassis interior with their venting directed inward.

Data Interfaces

There is very little published on the (Ω) and (C) terminals of the batteries, and so beyond speculation, these interfaces will need to be determined once the Alpha and potentially Beta stages are implemented and an ADC peripheral can be introduced to monitor system state. The ADC peripheral responsibilities may need to be split into two- one for the backend and one for the frontend given the range of voltages involved and that most COTS ADCs will only support the frontend voltages. This will entail a separate build/buy decision and design as an adjunct to the Power Subsystem akin to a GARP payload.

Physical Interfaces

Most of the Power Subsystem’s components will be physically installed on a DIN rail that should be adequate for the low speeds and vibration in the GARP intended use cases. That said, the primary exception to this is the Dual Charger which also includes the mass of the batteries. To fix the Dual Charger to the chassis, a keyhole style aperture could be installed, but I’m not confident this would provide adequate holding power without damaging the relatively soft plastic of the charger enclosure. Available space within the battery bay portion of the chassis is not very tight, so a solution for fixing the Dual Charger will be developed either at the end of the Alpha stage or during Beta, once all components (including the Motor Controllers and Navigation Computer) are in place.

Other than securing data and power wiring, which will be done with zip ties as an initial strategy, a panel-mount AC socket will be installed in the rear face of the GARP’s chassis and routed to the Dual Charger’s AC input to support connection without removing the GARP’s shell.

Summary

This article discusses the Power Subsystem design through at least the Alpha stage with some notes as to refinements to be completed in future stages. Requirements are briefly covered and the Kobalt 80V battery ecosystem is introduced. The Power Subsystem design is split into backend and frontend components with an intervening Intermediate Voltage (IV) designed to abstract the backend and provide more flexibility in introducing or modifying voltages fed to the front end. A strawman power budget is introduced to provide rough orders of magnitude of power consumption, runtimes, and relative burden on key components like backend DDCs and frontend Buck converters. A rough DIN rail layout is presented and other physical interfaces are touched on. The data interfaces of the Power Subsystem (e.g. battery temperature measured via thermistor) is left for a future design refinement once a prototype system is in place.