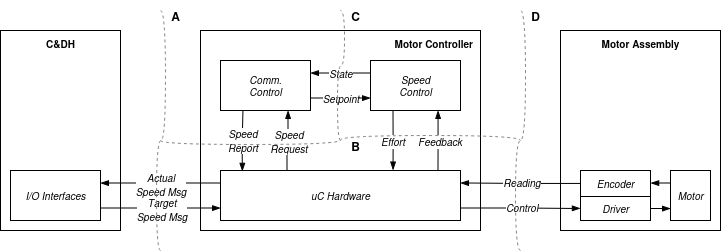

In embedded systems development, tightly coupling application logic to hardware-specific APIs often yields fast initial progress but complicates testing, debugging, and future hardware upgrades. This article details the motivations, design decisions, and benefits of implementing a Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL) for the GARP motor controllers, which communicate using CAN and are currently built around the RP2350 microcontroller and the MCP2515 CAN controller. Faced with integration challenges between the ros2_canopen package and hardware, limited visibility through standard tools like candump, and a lack of test coverage in upstream drivers, the author introduces a HAL to decouple application logic from hardware specifics. The HAL facilitates host-based testing, supports mocking, and allows clean portability to future platforms such as STM32 MCUs or the MCP2518FD for CAN FD support. The article provides real-world examples of interrupt and CAN controller abstractions, touches on their usage in test environments, and outlines future work needed to deepen test coverage and simulation capabilities.

GARP Article Series

The Ground Autonomy Research Platform (GARP) is a home-grown UGV designed and built to support independent learning of robotics and autonomy through a full stack from hardware to behavioral autonomy and HMI. To document the implementation of GARP, I’m capturing the process in a series of articles that I’ll link here as they’re completed:

GARP Article Map

- Motivations and Design of a UGV for Robotics Research

- GARP Power Subsystem

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

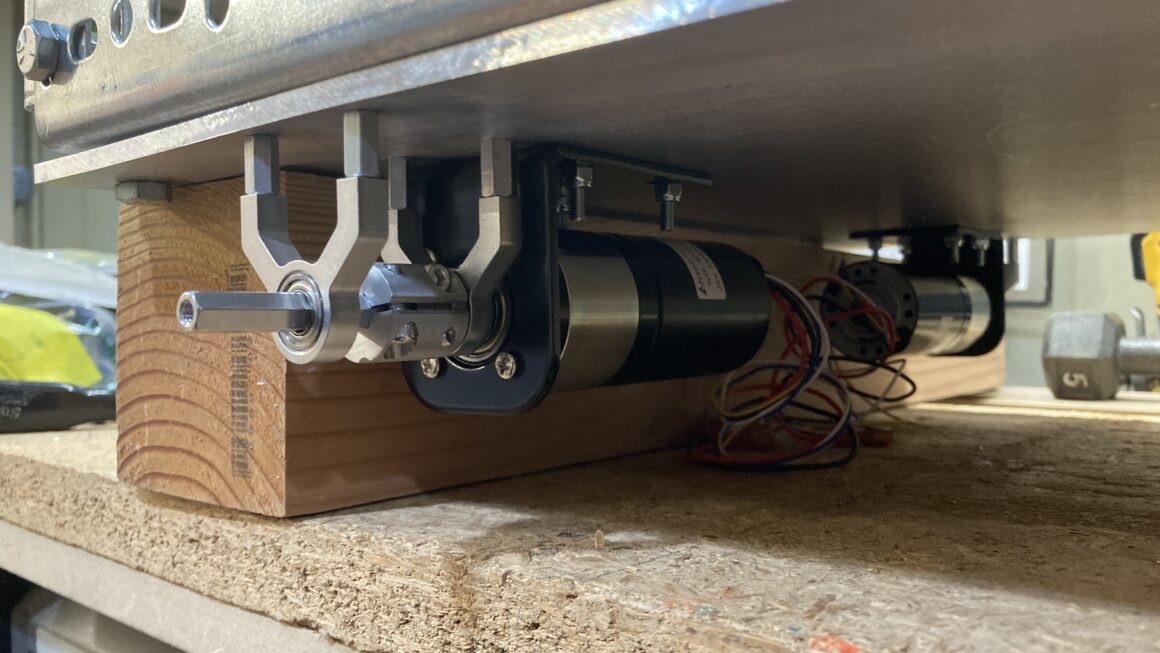

- GARP Mobility Subsystem

- Motor Selection

- Subsystem Design

- Motor Controller

- C&DH

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

- GARP E-Stop

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

Motivations

- Motivation for writing HAL (Why)

- Writing a HAL takes time and adds a layer of complexity to implementation- is justified by benefits in testing and future port to another mcu like STM or can transceiver like MCP2518FD to add 2 Mbps support

- While configuring the ros2_canopen package to integrate with the GARP MCs’ canopen implementation, kept hitting roadblocks with little context as to reason for failure

- candump was helpful but not adequate

- ros2 logs (particularly the Lely info) where somewhat helpful, but internal state was impacting

- GDB didn’t want to cooperate with debugging either the ros2_canopen or GARP sides

- Saw some odd implementation details in pico_mcp2515 such as setting read-only bits in registers, etc., but no tests found

- Needed to be able to test MCP instance and provide more hooks into state and operation

- Provide abstraction interface to support mocking/spoofing/faking and testing with and without HWIL

When developing embedded systems, it’s easy to dive straight into the hardware-specific code and get things working—until debugging becomes a nightmare or a new hardware requirement comes along. That’s exactly what motivated the creation of a Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL) for the GARP motor controllers (MCs): to make testing easier and to make shifting to alternate hardware simpler.

That said, writing a HAL introduces complexity and effort: it takes time, adds interface documentation requirements, and requires careful design to keep interfaces clean. But in exchange, you get several key benefits:

- Testability: Hardware-independent tests are easier to write and run and automate

- Portability: Switching from an RP2350-based controller to an STM32, or from an MCP2515 to an MCP2518FD (for CAN FD support), becomes significantly simpler.

- Maintainability: Problems can be isolated and tested at the boundary between hardware and application logic and frequent testing is easier to implement

These benefits became apparent during integration of the ros2_canopen package with the GARP MCs’ CANopen implementation. Configuration was flaky, and diagnosing failures was harder than expected. candump provided raw CAN traces, but often lacked the context needed and were copious. ROS 2 logs (especially from the Lely CANopen stack) were occasionally helpful but didn’t always capture the state information needed. Furthermore, GDB was not cooperative on either the ROS2 or hardware sides, particularly when coupled with the Raspberry Pi Debugging Probe. While conducting code forensics to attempt to tease out problems I also saw unexpected MCP2515 register access patterns such as writing to read-only bits. Finally the MCP2515 driver I was using did not have any testing shared in it’s repository.

To facilitate my better understanding of the MCP2515 driver’s logic as well as to hopefully provide traction in understanding the “secret handshakes” involved in configuring ros2_canopen, Lely, canopen-stack, and the MCP2515, I decided to shift focus to implementing a HAL.

The Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL)

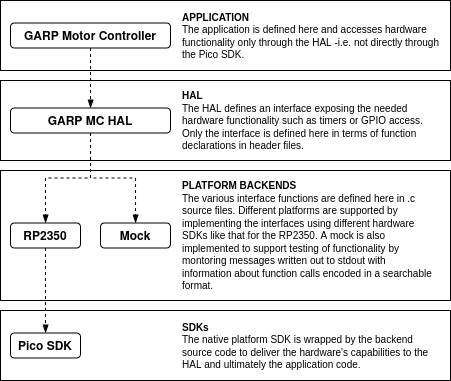

The GARP Motor Controller HAL is implemented in C with testing in C++ and GTest, and with its build managed in CMake. It serves as an intervening layer abstracting the application code from hardware-specific APIs. This allows application-level code to request hardware operations without specifying which hardware is being used (e.g. Raspberry Pi or STM microcontrollers). This abstraction provides an intermediate interface to support testing without target platform hardware. In general the HAL provides a flexible coupling of Application logic to hardware APIs:

At build time, static libraries are created for each implementation set. At link time, the appropriate library is selected:

- Testing on host: Link with

libgarp_mc_hal-mock.a - Deploying to RP2350: Link with

libgarp_mc_hal-rp2350.a

This setup allows the same application code to run either in a test harness or on real hardware, just by changing the link target.

To support this clean separation, each implementation directory (mock, rp2350, etc.) has its own CMakeLists.txt. These are pulled into the top-level build using ExternalProject_Add, enabling distinct toolchains (e.g. for x86 host vs RP2040 cross-compilation) without polluting each other’s build environment. See CMake ExternalProject_Add documentation for more details.

Even the CAN controller abstraction benefits. The MCP2515 driver used by GARP is built atop the HAL’s hal_can interface, meaning it too is decoupled from the RP2350. This makes it possible to test and verify CAN functionality—mocked or real—without committing to a particular hardware platform.

Example Usage

To make this a bit more concrete, consider a couple examples of how the HAL is used; First to abstract attachment of a callback to an encoder tick interrupt, and second to abstract use of the MCP2515 by the GARP CAN Controller.

The GARP PID Controller receives encoder ticks from the attached motor to indicate the output shaft has rotated by roughly one degree. These encoder ticks are collected by the PID controller and the accumulated counts are used to estimate the motor’s current speed, compare it to the desired speed, and adjust the PWM control signal sent to the motor’s integrated ESC. The encoder ticks are defined by a level change in the 3.3V signal from the motor to the microcontroller. To count these ticks, an interrupt is attached to the pin the encoder signal is connected to, such that each time a level change occurs on the signal line, the interrupt is called and the encoder (ticks) count is incremented. The Pico C/C++ SDK defines a series of functions to attach interrupts to GPIO pins, and these are wrapped by the HAL to produce the RP2350 implementation of the HAL Interrupt interface. The mock implementation is then implemented in parallel to allow running the PID Controller on (e.g.) a desktop computer that does not support the GPIO interrupt functionality of the Pico 2.

The HAL’s Interrupt interface includes the following function in hal_interrupt.h:

/*! @brief Attach interrupt to pin

@param pin Pin to attach interrupt to

@param event Event to trigger IRQ on

@param callback Function to call on IRQ

@param enable Whether to enable interrupt upon creation

*/

void attach_interrupt(const uint32_t pin,

const hal_irq_event_t event,

const hal_irq_callback_t callback,

const bool enable);This function accepts a GPIO pin number, a signal event type such as a rising edge or falling edge, a callback to execute when the interrupt is triggered, and an option to enable the interrupt immediately. For example, if one MCU only has rising and falling edge triggers, while another has rising, falling, high, and low triggers, these are abstracted by this opaque typedef that is only declared in the HAL’s interface header files, and can be defined in different ways in the platform-specific source code.

The mock implementation of this interface in hal_interrupt_mock.c simply dumps information about this function call to stdout via the (LOG_MOCK function); Specifically that it was called, and the arguments supplied:

void attach_interrupt(const uint32_t pin,

const hal_irq_event_t event,

const hal_irq_callback_t callback,

const bool enable) {

LOG_MOCK("Running R>attach_interrupt<R");

LOG_MOCK("Arguments:");

LOG_MOCK("A>attach_interrupt(): pin: %u<A", pin);

LOG_MOCK("A>attach_interrupt(): event: %u<A", event);

LOG_MOCK("A>attach_interrupt(): callback: 0x%x<A", callback);

LOG_MOCK("A>attach_interrupt(): enable: %u<A", enable);

};The Pico2/RP2350 implementation however, realizes the functionality using the Pico C/C++ SDK in hal_interrupt_rp2350.c:

void attach_interrupt(const uint32_t pin,

const hal_irq_event_t event,

const hal_irq_callback_t callback,

const bool enable) {

gpio_init(pin);

gpio_set_dir(pin, GPIO_IN);

gpio_set_irq_enabled_with_callback(

pin,

(uint32_t)event,

enable,

(gpio_irq_callback_t)callback);

};And yes, the C-style casts above are a bad idea (I plan to circle back and resolve these). Unfortunately even a HAL won’t magically allow one to forward declare a type interface when the underlying implementing types vary.

In testing, this will allow for confirmation that the callback is attached the to interrupt by linking the mock static library into the test executable, and checking stdout for the call to attach_interrupt().

As a second example, consider the use of the use of the HAL in the GARP CAN Controller and the MCP2515 driver. There are four modules in play:

- HAL CAN Interface: The HAL’s CAN interface declares the interface used to generically access the CAN device. This includes definition of a frame structure and general initialize, send, receive, and get errors functions

- MCP2515 Driver: The MCP2515 uses other parts of the HAL interface to implement the CAN interface and introduces the logic and configuration specific to the MCP2515’s operation

- CANopen CAN Driver: The CO driver uses the HAL interface (including the CAN interface) to implement the CAN driver interface (CO_IF_CAN_DRV) declared by the canopen-stack.

- GARP CAN Controller: The CAN controller uses the HAL CAN interface and CO driver to integrate the canopen-stack on the motor controller.

The HAL’s CAN API includes functions like can_send() in hal_can.h:

/*! @brief Send a CAN frame

@param inst CAN instance to send with

@param frm CAN frame to send

@return Number of bytes sent on success, -1 on failure

*/

int8_t can_send(const hal_can_ifx_t* inst, const hal_can_frame_t* frm);Here the interface declares that an interface “instance” is provided as well as a CAN frame to send. “Instances” like this are used throughout the HAL to manage state in configured devices like the CAN controller or a PWM generator. This opaque typedef abstracts the actual contents required for platform-specific operation of a piece of hardware into a single struct. As new platforms are supported, the underlying struct is implemented in a separate source file with the appropriate fields to support operation of the device.

The CAN interface is implemented in hal_can_mock.c and hal_can_mcp2515.c in a similar way to the interrupt interface. In this way, when switching to another platform, e.g. an STM32 with an integrated CAN controller, a hal_can_stm32.c implementation can use the STM’s SDK to realize the required functionality without needing to alter the GARP’s CAN Controller or CO CAN Driver software.

When testing the MCP2515 driver for example, the HAL’s register mocking allows for directly checking the intended values of registers after executing commands in addition to confirming functions are instigating the SPI calls expected. Consider testing that the mcp_send_message() function checks the value of the first transmission buffer’s control register (TXB0CTRL) to confirm it’s ready to accept a CAN frame for transmission:

TEST_F(MockSendTest, SendCheckFirstTxBuffer) {

// Confirm transmit buffers' availability are checked in cascading fashion

// Create transmit buffers and initialize to 'ready' by clearing 4th bit

// (TXREQ).

hal_write_register(NULL, 0x30, 0); // TXB0CTRL

hal_can_frame_t frm = {.id=42, .dlc=1, .data=0x00};

start_capture();

MCPStatus status = mcp_send_message(mcp_inst, &frm);

std::string output = stop_capture();

// Confirm Transmit Control buffer 0 (TXB0CTRL) is checked

EXPECT_THAT(output, ::testing::HasSubstr(

"[MOCK] A>hal_read_register(): reg: 0x30<A\n"));

// Confirm logic reports 'ready' with 4th bit cleared.

EXPECT_EQ(status, MCP_STATUS_OK);

}In this example the mocked register is created by writing to it (a register context that stores the register values is created in the GTest fixture’s SetUp method.) Then the start_capture() and stop_capture() functions capture stdout and use the HasSubstr Matcher to confirm that particular register was read. One feature missing from the HAL approach is support for order of operations, but it may be possible to support this in the future by incorporating a linking-based mocker like cmocka, assuming the HAL functions are still linkable if inlined.

Next Steps

The HAL in it’s current state has already facilitated testing, but several additional things need to be done, including:

- Better SPI Mocking: Right now, the HAL can verify that SPI calls are made, but not simulate full responses. Compared to the existing register mocking (which allows injection and inspection), SPI is a blocker for implementing deeper testing.

- Expanded Tests: More coverage is needed for both the GARP Motor Controller logic and the MCP2515 driver, particularly around reading messages, not to mention support for characterizing performance.

- Mock-Driven Development: Maturing mocking capabilities in the HAL will enable more complete testing without resorting to hardware-in-the-loop (HWIL) tests, while also potentially allowing hybrid and/or automated HWIL tests.

While initial implementations focused on a minimal design, the addition of a HAL has enabled better testing and introspection and will hopefully enable breaking through current roadblocks in configuring the ros2_canopen package.

This article describes the implementation and rationale behind introducing a Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL) in the GARP motor controller firmware. Initially motivated by integration difficulties with the ro

Summary

Implementing a Hardware Abstraction Layer for the GARP motor controllers has proven to be an essential step—not just for testability, but for clarity, portability, and long-term maintainability. What began as a response to opaque integration failures with ROS 2 and the CANopen stack evolved into a structured approach for decoupling application logic from hardware specifics. Through the HAL, I’ve been able to run embedded firmware logic on host systems, isolate and inspect internal interactions, and lay the groundwork for broader hardware support, including higher-bandwidth CAN FD and alternative microcontroller architectures.

While the initial implementation is already delivering value, several key areas remain for development—most notably enhanced mocking for SPI interactions and expanded test coverage for more nuanced behaviors. As the HAL matures, it will enable a shift toward mock-driven development and provide the scaffolding needed for robust, hardware-agnostic testing. Ultimately, the HAL has not only helped bring current debugging challenges into sharper focus, but is setting the stage for smoother development and greater flexibility in GARP’s future hardware and software roadmap.

By investing early in abstraction and test infrastructure, we’re building embedded systems that are not just functional, but also understandable, verifiable, and adaptable—qualities that pay dividends over the full lifecycle of the project.