This post discusses some rough requirements, design estimates, and envelop calculations intended to enable implementation of the Alpha stage of the GARP Motor Controller. Some key requirements are discussed, including internal and external interfaces, and rough estimates of loop rates in constituent CAN and PID Controllers are made. Discussion of PID loop tuning via rate control and encoder tick filtering are also discussed.

Introduction

The primary objective of the GARP Mobility subsystem is to build motor controllers from a bare-metal microcontroller and a BLDC motor. I’ll design and build these incrementally, with early builds intended to facilitate GARP integration and drive refinements in later iterations.

GARP Article Series

The Ground Autonomy Research Platform (GARP) is a home-grown UGV designed and built to support independent learning of robotics and autonomy through a full stack from hardware to behavioral autonomy and HMI. To document the implementation of GARP, I’m capturing the process in a series of articles that I’ll link here as they’re completed:

GARP Article Map

- Motivations and Design of a UGV for Robotics Research

- GARP Power Subsystem

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

- GARP Mobility Subsystem

- Motor Selection

- Subsystem Design

- Motor Controller

- C&DH

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

- GARP E-Stop

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

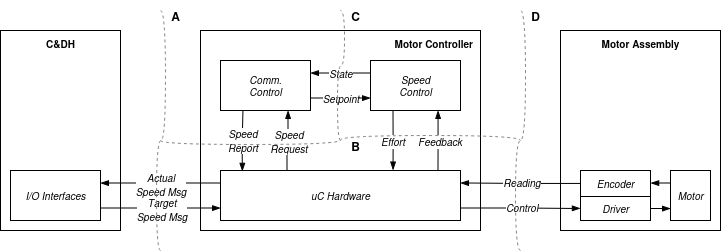

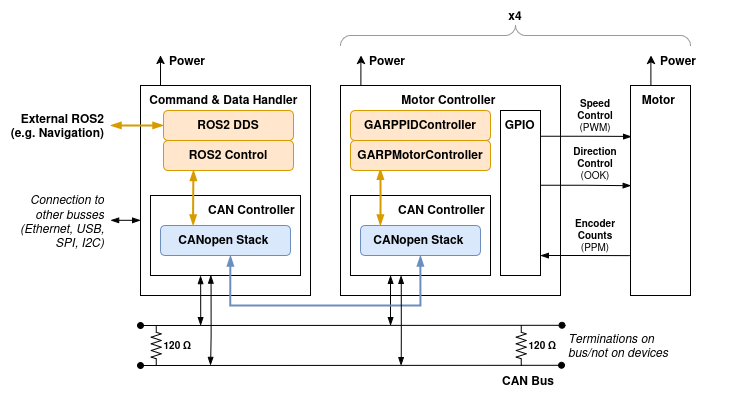

Within the Mobility Subsystem, the C&DH is responsible for interfacing between ROS2 and the CAN bus, specifically translating data from the ROS2 DDS (e.g. TwistStamped messages) to the CAN bus (e.g. CANopen TPDOs with object 6041h Target Velocity) for each wheel. The Motor Controller then takes instructions from the CAN bus, operates an objective-seeking controller (e.g. a PID controller), and produces the electrical signals necessary to drive the motor, such as Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) speed and On-Off Keying (OOK) direction signals. In the reverse direction, the Motor Controller provides actuals back to the C&DH, again via the CAN bus.

A note on terminology…

Velocity: The term velocity is used herein to be synonymous with rotations per minute (RPM) because the CiA 402 profile uses velocity- This is not to be confused with a linear platform velocity such as commonly published on the /cmd_vel topic. Because its being commanded in terms of rotational velocity, the MC does not need to know the wheel diameter. In the GARP, this translation occurs in the ROS2 Control Differential Drive Controller (DDC). This supports modularity of the system, as (e.g.) a change to wheel choice only needs to be updated in the GARP’s DDC configuration. Also note that the velocities are uniformly expressed in RPM. The only exception to this is in CANopen’s encoding of velocities which is handled via the dimension factor (Object 604Ch).

CAN and SPI Master/Slave: The terms Controller and Peripheral are used in lieu of the now outdated master and slave terminologies. When discussing SPI, MOSI and MISO now become PICO and POCI, respectively.

The Motor Controller needs to accept target velocities from the C&DH and translate them into signals to drive the attached motor. To do this the MC must first access and decode information from the CANopen Stack, and then must use this information to produce signals delivered to the Motor so the motor reaches the desired RPMs. The first half of this is relegated to the GARPCANController whereas the second half is the responsibility of the GARPPIDController.

Requirements/Constraints

To integrate with the rest of the GARP, the Motor Controller (MC) needs to satisfy several requirements tied to how it interfaces with the C&DH and its paired Motor. These are introduced here, and addressed below in the design and implementation discussions.

The MC will accept target velocities and report actual velocities from/to the C&DH using CiA 402. To do this it will need to implement the velocity encoding and decoding defined by the CANopen protocol. In the Alpha stage, only encoding and decoding will be implemented. In the Beta stage, the velocity model depicted in CiA 402 Figure 42 will be implemented in part or in whole, based on outcomes of Alpha. In v1.0 additional health reporting features will be added to provide context such as wheel slippage or motor current consumption.

The MC will need to accept input target velocities and report actual velocities at a minimum (threshold) rate of 10 Hz and a target (objective) rate of 20+ Hz so as to support contemporary navigation stacks. In the Wheeled Robot with CANopen and ROS2 Control: GARP Mobility Subsystem Design post, this update rate was determined to be within the art of the possible, but it is examined in more detail below.

This post also explores the use of heartbeats to trigger a motor reset and/or an M-stop, but the use of heartbeats is not otherwise required (in addition to e.g. RPDOs regularly responding to SYNC messages from the C&DH.)

Motor Controller Design

This abbreviated design section briefly touches on design decisions for those familiar with CANopen and embedded programming, but topics are linked to the relevant implementation sections that follow for more detailed discussion.

The GARP uses CANopen and specifically the CiA 402 profile to communicate between the Command & Data Handler (C&DH) and the Motor Controllers (MCs). This provides a ready-defined set of code words for communicating motion control-related information, but introduces the following additional burdens:

- Maximum of 127 nodes: The CANopen protocol uses 11-bits to define the unique identifier of nodes on the bus, limiting the total number of nodes to 127 (126 after assigning the controller)

- 6000h-block Object Dictionary additions: The CiA 402 profile defines object dictionary entries in the 6000h-block (in addition to those in the base CANopen 1000h-block). This consumes more memory on the resource-constrained microcontrollers.

That said, none of these are deal-breakers for GARP. There is unlikely to be 127 devices using the CAN bus on GARP, particularly given the priority of motor control and the desire to minimize latency of that control. The addition of more entries in the Object Dictionary could eventually pose an issue, but current implementations show only 6.6 kB of RAM used (of 520 kB on an RP2350):

arm-none-eabi-size garp_motor_controller_left_front.elf

text data bss dec hex filename

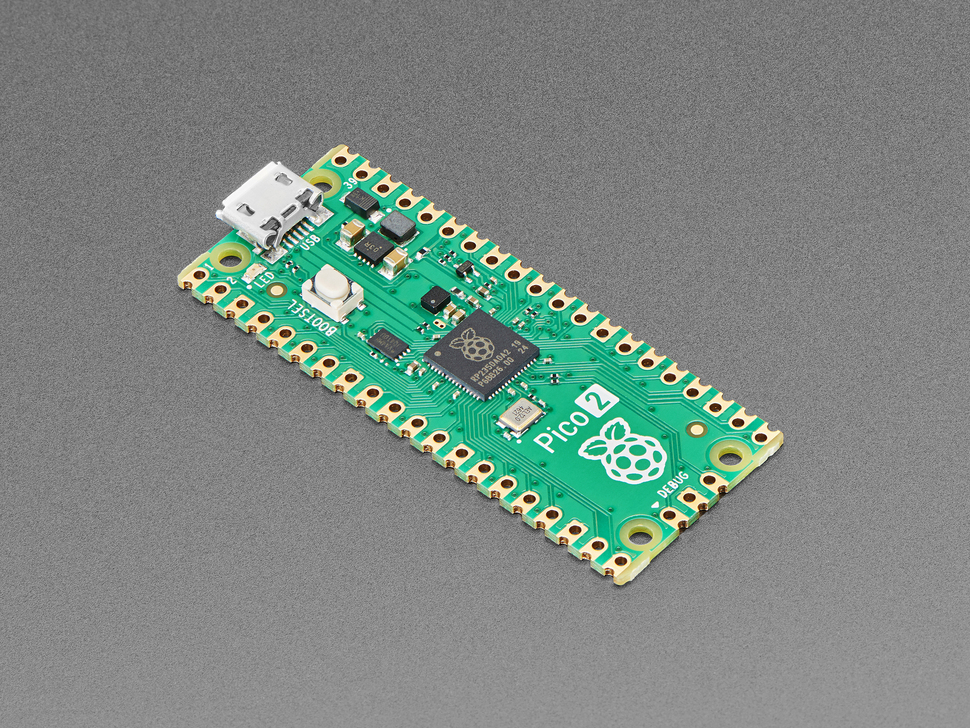

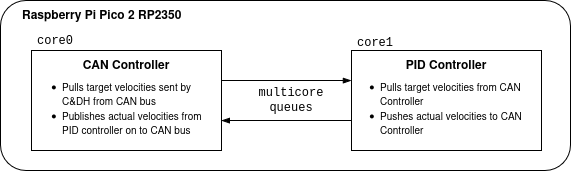

76624 0 6624 83248 14530 garp_motor_controller_left_front.elfThere are several CANopen implementations available as Free Off the Shelf (FOSS) software, so the question becomes which to use. The objective is to implement the MC on bare-metal (i.e. no Real Time OS/RTOS) so threading is a consideration. In parallel, due to personal familiarity, availability of CAN peripherals, and cost considerations, the Raspberry Pi Pico2’s RP2350 is a front-runner amongst the microcontrollers to use. The RP2350 has two cores capable of servicing timer and GPIO interrupts independently and sharing data via a FIFO buffer, enabling a design where a single-threaded CAN controller runs on one core, and a single-threaded PID controller runs on the other. This points to Embedded Office’s canopen-stack as a implementation choice (over say CANopenNode’s multithreaded implementation.)

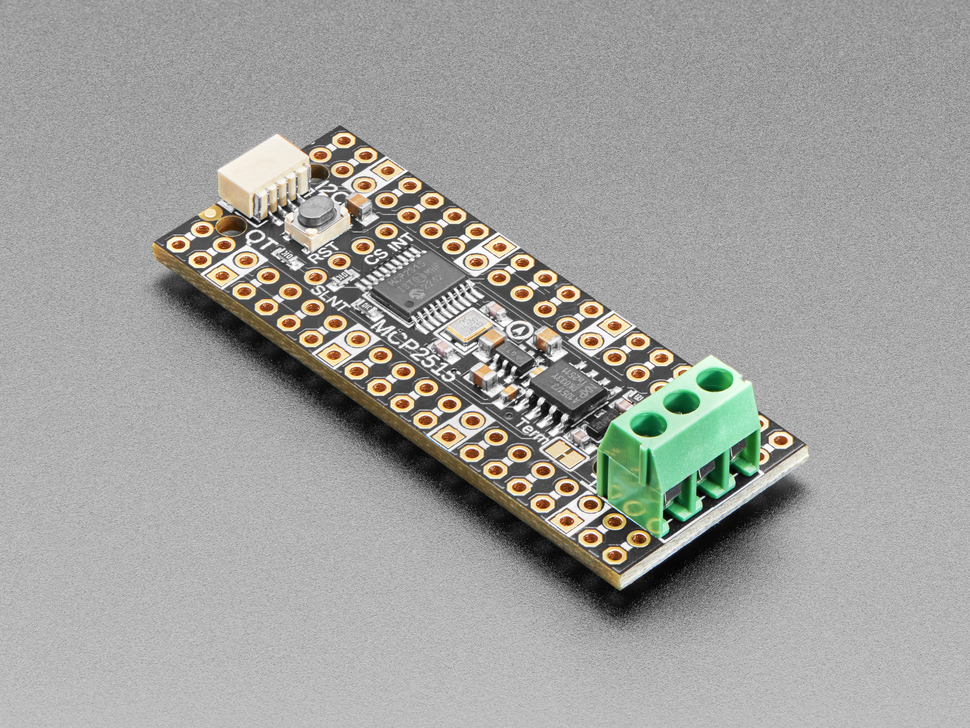

The MCP2515 is a common CAN controller, and Adafruit offers a PiCowbell CAN Bus featuring the MCP2515 Controller and TJA1051 CAN transceiver in addition to the Raspberry Pi Pico2 RP2350. Furthermore, a port of the MCP2515 library is available for the Pico on GitHub. One small complication of using this combination discovered during implementation (and discussed below), is the need to swap a delay() call with a busy_wait() so the reset() method can be used within an interrupt callback. To supplement this, a custom PCB will be created to provide voltage division and external power supply via the GARPs Power Subsystem.

Motor Controller Hardware Design

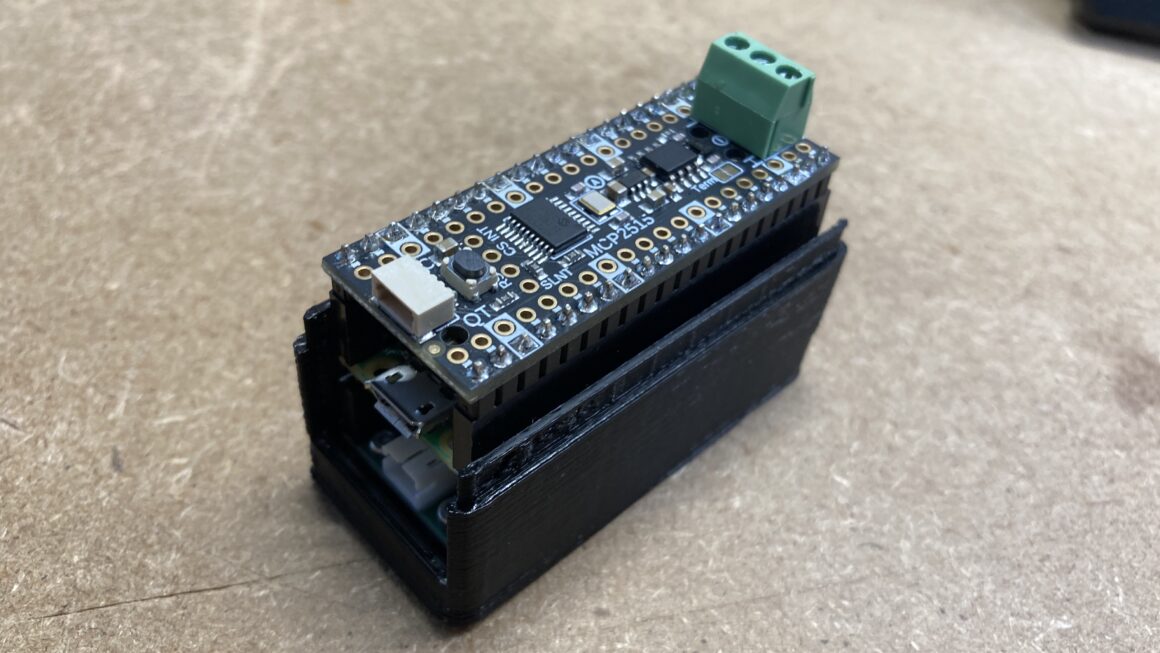

The Motor Controller (MC) hardware will be comprised of a Raspberry Pi Pico2 board, Adafruit PiCowbell CAN Bus shield, and a custom PCB to provide electrical integration support.

A particularly convenient aspect of the above boards is that when connected using stacking headers, all I/O pins are connected across the two boards, including on a custom stacked PCB. Given the software configurability of the pico2’s GPIO, this stacking means that the design process becomes (1) identifying the required functionalities, (2) using the Raspberry Pi Pico C/C++ SDK to find a collection of non-overlapping pin function assignments, and (3) making connections with intervening components (e.g. level shifters) on the custom PCB.

In the first step, the following functionalities are required:

CAN Controller Functionality

- CAN frame ready interrupt

- SPI communication (PICO, POCI, & CS)

Motor Controller Functionality

- Encoder transition (input) interrupt

- PWM speed control output

- Direction control output

In addition to these functionalities, we need the ability to supply power to the Pico via the VSYS pin and an external P-MOSFET as depicted in Figure 17 of the RP2040 Raspberry Pi Pico Datasheet.

To find a set of non-overlapping pins for step 2, we benefit from the fact that the PiCowbell is purpose-built to support the Pico2. By default, the CAN PiCowbell is configured to emit a CAN frame ready interrupt (the MCP2515’s INT pin) on pin 21, driving that pin low when a message is ready in either of the receive buffers, and held low until cleared. The pico-MCP2515 library handles this behavior such that only the interrupt must be registered. Furthermore, by default, the CAN PiCowbell uses pins 16, 18, 19, and 20 for SPI communication (POCI, Serial Clock/SCK, PICO, and Chip Select/CS, respectively) which align to spi0 in the C/C++ SDK.

In order to find pins for the encoder interrupt, PWM speed control, and direction control, we consult the RP2350 function selects table in the hardware_gpio API section of the Pico SDK documentation. Avoiding the pins claimed by the CAN controller above, I (somewhat arbitrarily- they’re contiguous and on the other side of the PCB from the CAN controller pins) chose pins 6, 7, and 8 to serve as the motor interface, where pin 6 is the PWM output (function F4/PWM3A from the RP2350 function selects table), 7 is the encoder interrupt, and 8 is the direction output pin.

The traces to support these few motor interface connections, including a voltage divider to bring the encoder output down to 3V3 logic, and traces to connect the P-MOSFET for fit easily into the space of the custom PCB, particularly when using surface mount devices (SMDs), and are discussed in the implementation section.

CANopen Stack Design

The primary effort in implementing the canopen-stack on the RP2350 revolves around implementing the CAN, Timer, and non-volatile memory (NVM) hardware drivers as discussed on the canopen-stack website. These are fairly straight-forward, but the Timer driver introduces a few design choices: The first is whether to implement a “cyclic” or “delta” timer method, and the second is which of the various timing features of the Pico SDK to use.

The cyclic timer method effectively maintains an internal counter for each software timer instantiated by the canopen-stack, incrementing them each time the hardware timer interrupt is called until the timer reaches its expiration. In this configuration the timer duration resolution available to the stack is given by the duration of the assigned hardware timer, and the timer interrupt is called much more frequently than in the delta method. In the delta method, the software timer is created with a specified duration, and the timer interrupt is called once when that duration has elapsed. This reduces the frequency with which the timer interrupt is called, but (assuming implementation with a function like add_alarm_in_us) would limit the number of concurrent software timers to the number of alarms available on the RP2350. Given that the software timers are expected to be used for numerous different timed events like heartbeats and message response timeouts, and the relatively low speed (1 Mbps) of the planned CAN Standard bus, the cyclic method is chosen. If the bus is upgraded to CAN-FD in the future, this may need to be reconsidered.

The decision of which of the SDK’s timer feature to use to drive the recurring timer is relatively inconsequential at this point; The two simplest options are the add_alarm and repeating_timer APIs. Both can be configured to repeat a prior timer from within the callback, by returning a new timer duration in microseconds in the case of the add_alarm functions, or by returning true in the repeating_timer functions. The add_alarm series do directly support passing a user data pointer to callbacks which is convenient for passing a handle to the CAN Controller instance, but given the repeating nature of the cyclic timer method, the purpose-built repeating_timer functions will be used.

Use of a CANopen heartbeat will be enabled to support canopen-stack hardware driver implementation and will remain in place until it can be used to trigger an M-stop on lost connection between the C&DH and Motor Controller (MC) in the Beta or v1.0 stages. While this will consume additional bandwidth, the heartbeat messages are simply the 11-bit COB-ID and a one-byte status code, such that a 1-2 second heartbeat’s impact (even when concurrently emitted by four MCs and the C&DH) should be minimal.

The CiA 402-prescribed TPDOs and RPDOs will be implemented via the ros2_canopen‘s bus.yml file (i.e. not in the C&DH’s/controller’s DCF file), and will be matched to the implementations of the MCs’ object dictionaries. The primary benefit of this decision is removing the need to hard-code the PDO’s communication and mapping configurations in the DCF and (MCs’/peripherals’) EDS files.

PID Controller Design

In the Alpha stage, the PID Controller is intended as a placeholder to facilitate integration and higher-level (e.g. ROS2 Control) control configuration. A simplified PID controller will be implemented on the second core of the RP2350 and exchange data with the CAN controller over a pair of queue objects:

The PID control loop rate also needs to be considered; If too slow, the PID controller will introduce latency into control of the GARP, and if too fast, it could outpace the motor encoder, causing issues such as jerky motion. The PID controller implemented will need to include some means for moderating loop speed, while also allowing it to free-run if necessary. While behavior will be tuned in later phases, initially consider the operating points defined by the input target velocities (e.g. via /cmd_vel) and the number of ticks issued by the encoder between iterations of the PID loop:

- We’ve used 10-20 Hz as a planning factor for the target velocities arriving on the CAN bus from the C&DH and Navigation stack, so we can use that as a minimum planning factor here (although in practice, we’ll likely want a higher rate to allow the motor’s actual speeds to home on the desired targets)

- For the selected motor, the maximum rated speed is 5 RPS and with the planetary gear, issues 300 encoder counts per wheel revolution. This means that at it’s highest speed a motor’s encoder ticks will arrive at 1.5 kHz. If we want at least 100 resolvable points in speed control, we can estimate 15 Hz as a upper limit on the PID loop speed. This is fairly slow, so we’ll likely need to implement some sort of filtering such as a moving window to enable higher loop rates (albeit at the expense of control latency.)

The PID Controller will also require some passive electronics to provide voltage pull-up and division on the encoder line, as well as routing signals to the appropriate pins as discussed in the Hardware Design section. This should introduce little additional software, besides some pin definitions and configuration.

Summary

This post discussed some key requirements in the development of the Motor Controllers (MCs) for the GARP, including external interfaces with the Command and Data Handler (C&DH) and internal interfaces between the CAN Controller and PID Controller. Rough estimates of the rates at which the CAN and PID controllers will need to operate were made, and the likely need for loop rate control and filtering of encoder ticks was identified. The message objects and PDOs to be used (at a minimum) were also identified. This should be enough guidance to get us through an initial implementation of the Alpha stage, where the design can be refined based on integrated GARP operation.