The GARP uses a CAN bus and the CANopen protocol to communicate between a central Command and Data Handler (C&DH) and the wheels’ Motor Controllers. This post captures the highlights of the design process used to make build/buy decisions, select components, and make other design decisions. The post begins with the design principles and assumptions made specific to the Mobility Subsystem and the strategy employed. Brief discussions of phased development as well as CAN vs CAN-FD and the CANopen protocol are included along with BLDC integration and PCB design. This post builds on the Mobility Subsystem Design article and lays groundwork for the Motor Controller and C&DH detailed design and Alpha-level implementation posts.

Introduction

The primary objective of the GARP Mobility subsystem is to build motor controllers from a bare-metal microcontroller and a BLDC motor. A central challenge will be to be responsive to hardware conditions like encoder resolution and electrical signalling levels. I also want this to serve as an introductory project in communication over a CAN bus.

GARP Article Series

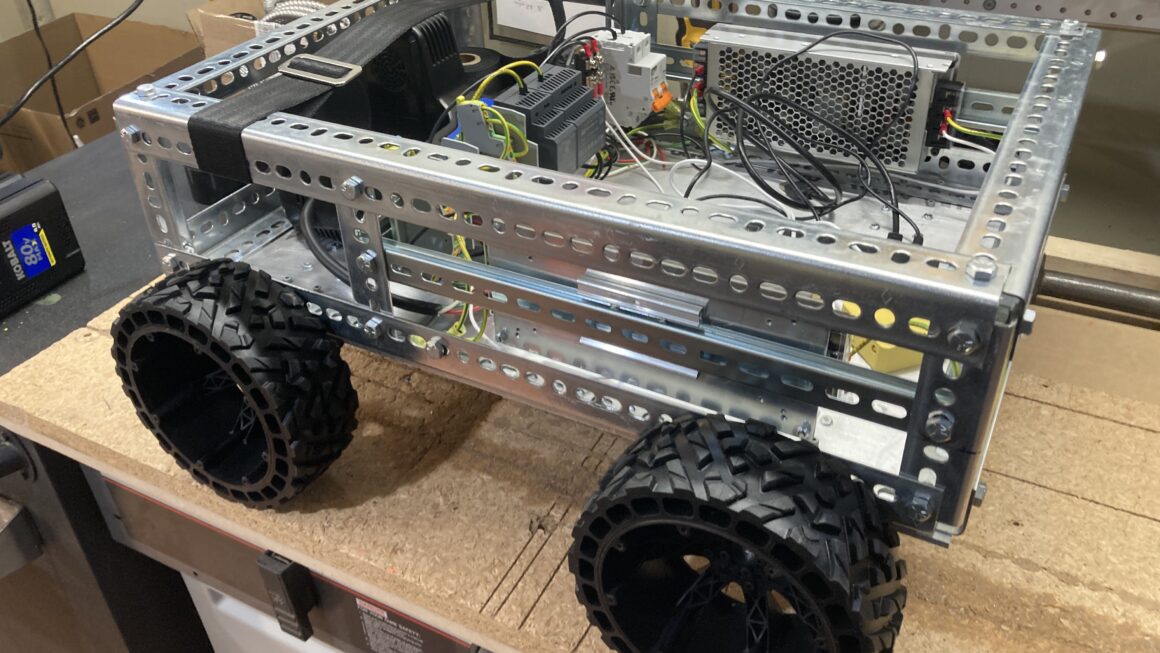

The Ground Autonomy Research Platform (GARP) is a home-grown UGV designed and built to support independent learning of robotics and autonomy through a full stack from hardware to behavioral autonomy and HMI. To document the implementation of GARP, I’m capturing the process in a series of articles that I’ll link here as they’re completed:

GARP Article Map

- Motivations and Design of a UGV for Robotics Research

- GARP Power Subsystem

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

- GARP Mobility Subsystem

- Motor Selection

- Subsystem Design

- Motor Controller

- C&DH

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

- GARP E-Stop

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

Design Principles Specific to the Mobility Subsystem

A key objective for the GARP Mobility Subsystem design is to establish a microcontroller development and testing process including rapid develop, test, and deploy cycles. In particular, I’d like to accomplish automated hardware-in-the-loop (HWIL) testing of microcontroller-hosted applications.

I’ll use ROS2 for the higher-level autonomous behaviors of the GARP, and to interface the Mobility Subsystem with ROS2 I’ll use ROS2 Control. I’ve had some prior exposure to ROS2 Control, and see a lot of promise, so I want to use GARP to motivate a deeper exploration. A key appeal of ROS2 Control is the modularity of the controllers and the ease of moving between simulation and real hardware; I can simulate the GARP in Gazebo using the same model and make a few parameterized changes in the URDF and launch files to run on actual hardware. Furthermore, the option to incorporate sensors in ROS2 Control is also appealing for when I implement the perception subsystem on GARP.

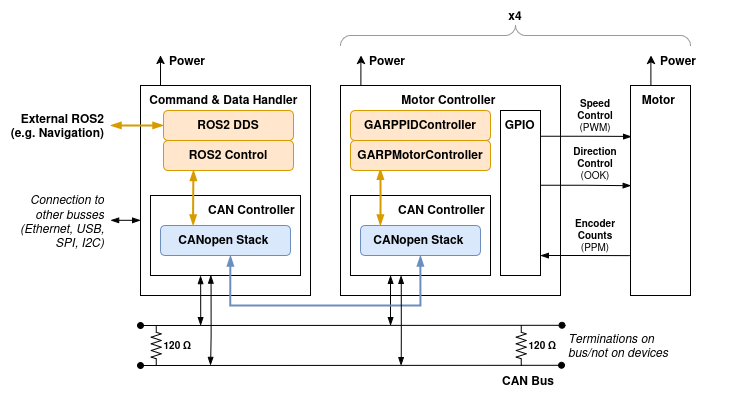

I’d also like to explore the use of the CAN bus, and to do so on GARP, I’ll use the CiA 301 CANopen protocol. As I’d need to establish a code words for various instructions in CAN anyway, using CANopen will provide that out of the box. To accelerate prototyping, there are various existing implementations of the standard including canopen-stack and CANopenNode, and ROS2 Control integration through packages like ROS2 CANopen. Furthermore, the CiA also hosts profiles like CiA 402 for motor control with a fine-grained set of mobility-specific code words. That said, two key considerations will be (a) the amount of processing power required to support the stack at a responsive rate, and (b) the amount of work required to configure the stack.

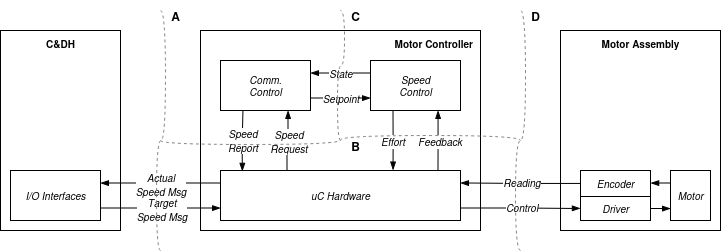

With these principles in mind, we arrive at the following top-level Mobility Subsystem design; The Subsystem is composed of the Command & Data Handler (C&DH), the Motor Controllers (MCs), and the motors.

Within the Mobility Subsystem, the C&DH is responsible for interfacing between ROS2 and the CAN bus, specifically translating data from the ROS2 DDS (e.g. TwistStamped messages) to the CAN bus (e.g. CANopen TPDOs with object 6041h Target Velocity) for each wheel. The Motor Controller then takes instructions from the CAN bus, operates an objective-seeking controller (e.g. a PID controller), and produces the electrical signals necessary to drive the motor, such as Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) speed and On-Off Keying (OOK) direction signals. In the reverse direction, the Motor Controller provides actuals back to the C&DH, again via the CAN bus.

Design Strategy

In alignment with the GARP’s iterative development strategy, I’ll push the Mobility Subsystem through Alpha, Beta, and v1.0 stages. The Alpha stage will produce breadboard components primarily intended to support concurrent development, evaluate design choices, and rapidly discover any significant design changes needed. The Alpha stage will support design insights such as:

- Discovery of impacts from external factors like power transients from the Power Subsystem

- Required robustness of connectors and cabling like JST terminals versus screw terminals

- Sufficiency of CAN Standard (1 Mbps) or need for CAN-FD (2.5+ Mbps)

At the Alpha stage, I’ll be able to run the individual components of the Mobility Subsystem and integrate them, running the GARP on blocks where the wheels can move freely without platform motion.

For the Beta stage I’ll produce brassboard components to enable testing and characterization of individual components and the integrated Mobility Subsystem. Again running on blocks, the Beta stage will allow testing and characterization such as:

- Measuring run time and characterizing energy consumption in different battery configurations

- Probe for failures only occurring with extended run times

- Find performance bounds of CANopen configurations like target and actual velocity update rates

- Dry-running field use protocols like boot-up sequences and interlock/e-stop activation

The v1.0 stage will produce a prototype Mobility Subsystem that can be used for field testing and characterization of the GARP. This will include a skin and skid plates and the hardening necessary to survive exterior conditions. This will also be the first time the GARP’s mechanicals are exposed to the forces of protracted operation including (hopefully few) impacts and drops. The v1.0 stage will also allow for characterization in field environments like e-stop ranges and the impact of real factors like traction loss.

Envelope Calculations

The GARP’s Mobility Subsystem is depicted in more detail below:

The CAN bus is the primary means for transferring digital data between the C&DH and Motor Controllers. The maximum bitrate under CAN Standard is 1 Mbps or a 1 us bit duration. To consider the bandwidth consumed by the motor control instructions and returned status and actual velocities, I need to look at the CiA’s 301/CANopen standard and how it will be applied on GARP.

More Info: CANopen SDOs & PDOs

When transmitting data over CANopen, either Service Data Objects (SDOs) or Process Data Objects (PDOs) can be used. Generally, SDO frames include a 43 bit header with the information necessary to request a specific piece of data from a node on the CAN bus in addition to a 4 byte payload. In contrast, a PDO frame can combine multiple specific pieces of data and reduces the header information transmitted to 11 bits by configuring the transmission in advance. The result is that PDO frames are up to 4 times more efficient bandwidth-wise for recurring transmission of data, and can be triggered on a regular basis using SYNC frames. For more information, a high-level overview of CANopen, SDOs, and PDOs can be found here and the CANopen CiA 301 standard can be found here.

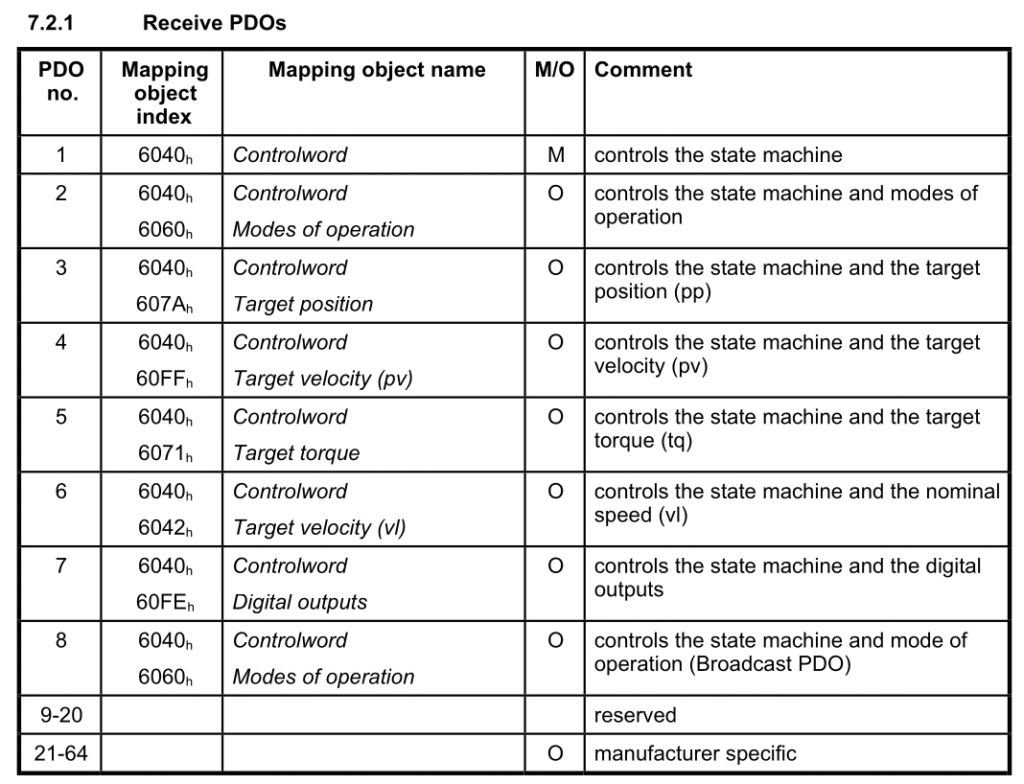

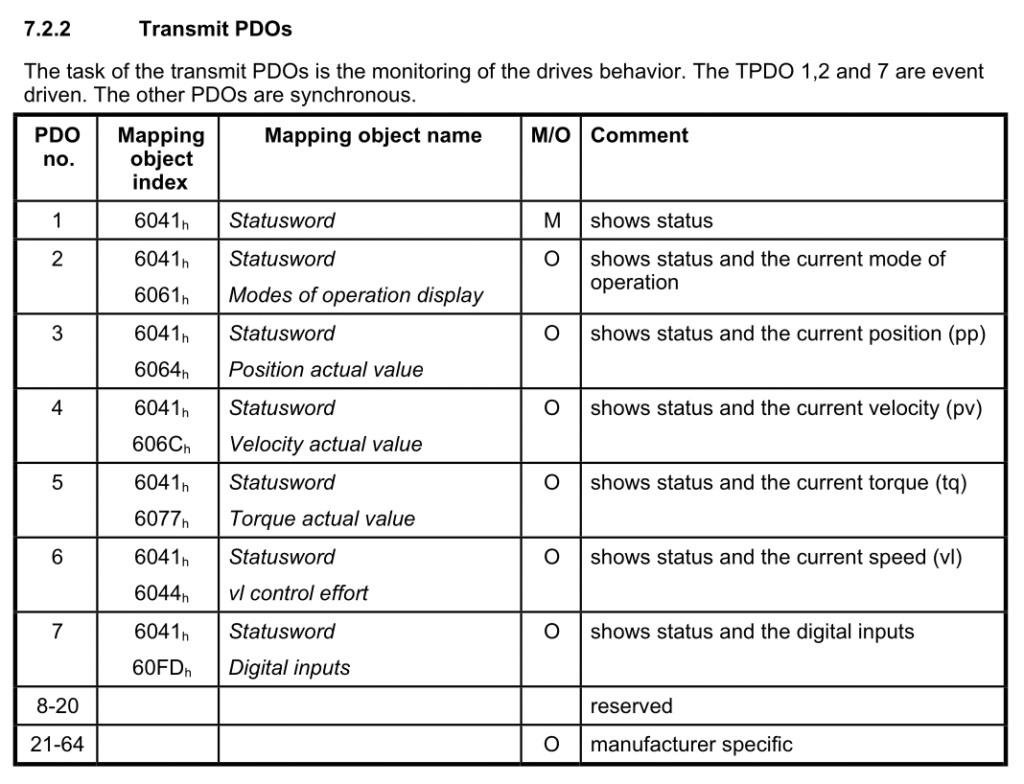

In particular to the GARP, given that target velocity is expected to be issued at a regular rate (e.g. 10-20 Hz from a navigation stack like nav2), a C&DH-issued SYNC and PDOs could be used to transmit target velocities to the motors and collect their actual velocities. To evaluate the feasibility of using CAN Standard for communicating with the Motor Controllers, consider the bandwidth used if applying the CiA 402 profile for drives and motion control which provides standard PDOs and objects:

More Info: CANopen Objects

In CANopen, data is identified in terms of objects and specified via a 16 bit index and 8 bit sub-index. This data is registered in Object Dictionaries local to each device on the bus. Objects can include device names, configuration of PDOs, or specific values such as target or actual velocity. For example, the GARP’s Motor Controllers use an Object Dictionary defined in the GARPCANController header file and the C&DH stores it’s (initial) Object Dictionary in a DCF file.

To estimate CAN bus bandwidth use, we can expect each Motor Controller to require at least RPDO #6 (6042h: Target velocity) and TPDO #4 (606Ch: Velocity actual value). Objects 6040h, 6042h, 6041h, and 606Ch are transmitted as 16-, 16-, 16-, and 32-bit values, respectively, resulting in a total of 360 bits of payload sent per update or 3.6 kbps for a 10 Hz SYNC. Given that this is two orders of magnitude less than the 1 Mbps CAN Standard bit rate, use of CAN Standard appears feasible and worth prototyping.

Electrical Interfaces

When interfacing with the selected ES-42PG4260BL motor, bare wires for power, control, and encoder output are provided. In particular, the connections provided are:

| Wire Color | Function | Interface |

| Red | Power | 21.6-26.4 V |

| Black | GND | |

| Blue | Speed Control Input | 5V or 3V3 logic; PWM @ 20 Hz |

| Yellow | Encoder Output | 5V pull-up; PPM |

| White | Direction Control Input | 3V3 or 5V logic; OOK |

To support the connection and re-connection expected during development of the GARP, a JST connector will be used to connect the control and encoder wires, and quick-connects will be used to connect the power wires to the power subsystem’s 24 V supply. Some sort of strain-relief will be needed, but these won’t be incorporated until the Beta or v1.0 stages, and likely via secondary connectors fixed to the Motor Controllers’ housings.

To connect signals between the Motor Controllers’ microcontrollers and motors, a custom PCB will be produced. Depending on the microcontroller selected, voltage level shifters and a pull-down may be required on the PWM/speed control line, although the Alpha stage will likely use voltage dividers and a software configured pull-down.

The microcontroller and CAN controller and transceiver will be connected in a similar way, but will depend on the hardware selected. Furthermore, if shielding the CAN lines, their shielding will need to be grounding on one end, and ground loops should be avoided. The selected CAN controller will ideally also include the transceiver and either be onboard the microcontroller PCB, or at least be a “shield”, “hat”, etc. to minimize wiring complexity and simplify physical anchoring.

Physical Requirements

To enclose the Motor Controllers, a custom 3D-printed PLA case can be used per each motor controller. In the Alpha stage, PCB-mounted terminals can be interfaced directly, while the Beta stage can add hops from the PCB-mounted terminals to case-mounted connectors. The v1.0 stage then add hardened and/or sealed connectors.

To avoid interference, power and data cables will be routed separately. The Alpha stage will route cables but leave them free as frequent movement is expected, and the Beta stage can fix the wires in place with zip ties. v1.0 an either continue the use of zip ties or move to a more permanent option based on the frequency with which the cabling is altered.

Finally, the fix the motor controllers within the chassis, I’ll use a hook-and-loop fastener in the Beta stage and consider permanent attachment like DIN rails in the v1.0 version.

Summary

The GARP uses a CAN bus and the CANopen protocol to communicate between a central Command and Data Handler (C&DH) and the wheels’ Motor Controllers. This post captured the highlights of the design process used to make build/buy decisions, select components, and make other design decisions. The post begins with the design principles and assumptions made specific to the Mobility Subsystem and the strategy employed. Targeted achievements/maturity levels are outlined by phase and the use of CAN (vice CAN-FD) and the CANopen protocol are discussed. BLDC integration via custom PCB is introduced.