This article presents a modular software interface architecture for the motor controller in the GARP robotics platform. The design separates the system into three cooperating components—Communication Controller (CC), Speed Controller (SC), and Motor Controller (MC)—each with clear boundaries and responsibilities. These boundaries are defined to support modularity and accelerate future development. The design aims to support portability, testability, and code reuse across various embedded platforms and adjoining subsystems. Implementation details and examples are provided to ease use. The interface currently supports velocity control mode, but extension to position and torque control modes in the future are possible, with the objective of minimizing the need for whole-cloth rewrite or even significant refactoring.

GARP Article Series

The Ground Autonomy Research Platform (GARP) is a home-grown UGV designed and built to support independent learning of robotics and autonomy through a full stack from hardware to behavioral autonomy and HMI. To document the implementation of GARP, I’m capturing the process in a series of articles that I’ll link here as they’re completed:

GARP Article Map

- Motivations and Design of a UGV for Robotics Research

- GARP Power Subsystem

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

- GARP Mobility Subsystem

- Motor Selection

- Subsystem Design

- Motor Controller

- C&DH

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

- GARP E-Stop

- Design

- Alpha Implementation

Motivation

The primary motivation for the GARP is to support learning and as such it’s design and implementation should support enough modularity to allow a focus on learning the subsystems and components being integrated, and minimize time spent on integration. Some rework is expected, but ideally, each new motor controller implemented won’t require significant refactoring of adjacent (or non-adjacent!) components. This is complicated somewhat by the wide array of approaches available for functions like speed control and communication between components. Examples mentioned in other articles include PID and EKF speed controllers, as well as CANopen and MicroXRCE communication. This is compounded by the breadth of hardware available for moving robots including like brushed and brushless motors, single and quadrature encoders, and various driver/Electronic Speed Controller (ESC) interfaces. This also covers the breadth of hardware used to host the logic for these controllers such as different microcontroller ecosystems. This article focuses on outlining the design and implementation of a set of modular, reusable motor controller interfaces to support modularity objectives across the breadth of potential communication and speed control options.

On the GARP, the motor controller is responsible for providing control signals to the motor driver to cause the output shaft to rotate at a desired speed. For the time-being there is no requirement to operate in a position control or torque control mode, although they may be added in the future. As part of this speed control responsibility the MC accepts feedback from an encoder to estimate an actual motor shaft speed, as required to seek a target speed goal, but also to support odometry measurements of shaft (and thereby wheel) rotation.

The MC should also manage a communication interface with the C&DH to accept target speeds and to report actual speeds. This communication control responsibility includes management of the connection to the C&DH, including operations such as initiating and terminating communication channels and translating between message formats.

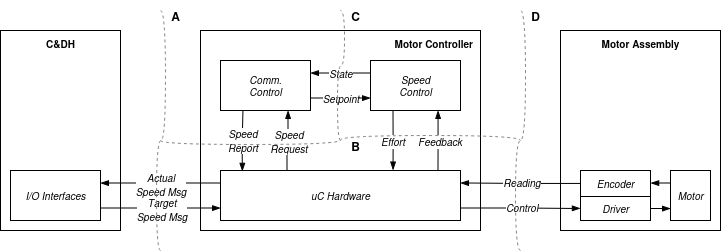

These two core responsibilities are shown in the functional diagram below:

The next few subsections will discuss each of these boundaries, working from the outside-in.

Boundary A: Command & Data Handler (C&DH) to Motor Controller (MC)

The interface between the C&DH and MC is marked by a gray dashed line labeled “A”. The key communication across this boundary is the reception of target speed messages from the C&DH and transmission of actual speed messages from the MC. These messages allow the GARP to (1) direct the wheels to rotate at desired speeds and (2) to use odometry to estimate the GARP’s position over time. As the primary function of the GARP is to facilitate learning, the channel over which these messages travel is expected to vary, although the initial “short list” to support is CANopen and Micro XRCE protocols. This interface is expected to always be digital, but the physical layer (e.g. number of conductors) may vary depending on the protocol used. A Communication Controller (CC) will be responsible for logic tied to management of the messaging interface with the C&DH.

Boundary D: Motor Assembly (MA) and Motor Controller (MC)

The interface between the MA and MC is marked by a gray dashed line labeled “D”. This interface is defined by the transmission of control signals to the motor driver (e.g. an ESC) and the reception of encoder signals. These signals allow the MC to (1) direct the motor with a given effort, while also (2) adjusting the provided effort signalling to better match the motor’s output speed to the goal provided by the C&DH. The motor controller is the primary system interface with the GARP, with other interfaces being power supply from the Power Subsystem and mechanical interfaces that are otherwise neglected here (see GARP Motor Selection for more info on mechanical considerations as related to the mobility subsystem.)

Encoder to Motor Controller

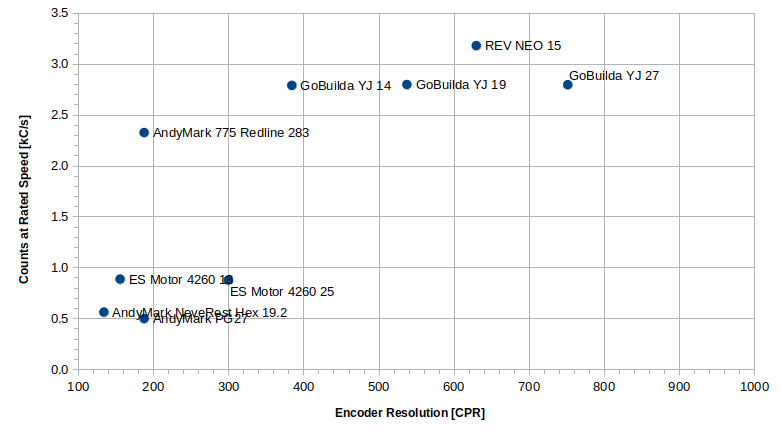

The MC design will assume the presence of an attached encoder that will provide signals as an analog of motor speed. It is expected these encoder signals could be in single line or quadrature formats and could include deadzones or arming zones. Encoder signals will likely be metered via GPIO line interrupts, but could also be measured via timers and a state machine (e.g. for direction on quadrature encoders) and could potentially be available via serial interfaces. The relation of arrival of encoder counts to wheel rotation may vary (as the encoder may be connected to the motor shaft or to a gearbox’s output shaft).

This said, the expected maximum rate of encoder count arrival can be estimated as the product of 500 wheel rotations per minute (RPM) and a maximum of 2000 encoder counts per rotation (CPR) for the encoders sampled previously (c.f. GARP Motor Selection), or <10 kHz as shown below:

Motor Controller to Driver/ESC

The MC will be responsible for producing the signalling necessary to realize the desired goal wheel rotation speed as supplied by the C&DH. To do this, the motor controller will need to produce control signals using microcontroller hardware in a protocol accepted by the motor driver used in the motor assembly. The encoder and driver are expected to be selected in tandem with the motor itself, although they may not be in a single enclosure- For example:

- The ES Motors 4260 BLDC (link) includes an integrated single channel encoder on the motor itself (not the gearbox output) as well as an integrated ESC accepting PWM signals for effort control.

- The goBilda Saturn BDC (link) uses an external two-channel speed controller (link) accepting PWM input, but integrated quadrature encoder on the motor shaft.

The speed control is expected to accept PWM input, but could accept any type of input include a serial protocol or analog input, as well as different PWM carrier frequencies, duty cycles/timings, and/or deadzones and arming zones.

Boundary C: Communication Controller (CC) and Speed Controller (SC)

The interface between the CC and SC is marked by a gray dashed line labeled “C”. The primary information exchanged across this interface is (1) state information for the SC and MA, as well as (2) a motor speed setpoint relayed by the CC from the C&DH. This interface is internal to the MC and has to most flexibility in definition as it does not connect with external C&DH or MA hardware, and is in fact a purely data interface, as it does not involve host microcontroller GPIO. Ideally, this interface would include some sort of queue or buffer to allow the CC and SC to operate asynchronously, posting their respective outputs as available.

Boundary B: Microcontroller (uC) Hardware Interface

The interface between the CC, SC, and uC hardware is marked by a gray dashed line labeled “B”. This interface passes speed requests and (actuals) reports to/from the CC and feedback and effort data to/from the SC. This interface allows for a data message from the C&DH (e.g. a Float32 RPM from MicroROS) to be communicated between the C&DH and MC, and then be used to produce a PWM duty cycle necessary to realize a given wheel rotation speed at the MA. The existing GARP HAL already provides an abstracted definition of this interface, which can then be used to port the MC to another uC hardware platform without altering the MC application software, while also providing convenient mocking for testing MC component logic.

Abstraction of interfaces

In the same way that the abstraction of the GARP MC HAL interface introduces modularity in the form of allowing porting application code to another hardware platform, the other three interfaces described above should also be abstracted. This will allow the components to be swapped without impacting other components (neglecting potential configuration tuning.)

For example, to explore use of an EKF instead of a PID-based SC, by abstracting interfaces B and C the alternate SC could be swapped in to the existing application code with minimal changes to accelerate development and characterization. Similarly, new motor assemblies could be evaluated through abstraction of interface D, as well as different C&DH-MC communications by abstracting interfaces A and B. While this stands to complicate the solution, the benefits will be become apparent while trialing new approaches to implementing any of the scoped responsibilities.

Design

The GARP MC HAL satisfies the desired abstraction of the uC hardware from the MC application (“B” in the diagram above), but the others still need to be designed. One benefit of the HAL is that the interface from C&DH-to-MC-to-CC can be simplified to the interface of the C&DH-to-CC. Other than use of the existing HAL, the design assumptions are:

- Implement in C for portability: The HAL is already in C and therefor can build on this to maintain portability. The OOP features of C++ can be handy when building interfaces, as are the smart pointers, but careful implementation in C should be feasible.

- Introduce copious testing: See the should above.

- Make easy to use: I’m finding myself context switching a lot- Bouncing between implementing MicroROS communication over UART, to designing PCBs, to LoRa wireless for an E-stop controller, to a Python-based data curation tool; I need to be able to quickly spin back up on the interfaces and understand workflow; Doxygen API documentation at a minimum, with an objective of implementation examples; Key take-away- avoid needing to go into source code to use the interfaces (including header files)

- Use link-time modularity: This results from the use of C, as polymorphism isn’t available; Note that this limits us to the use of a single type of CC and SC per application (otherwise we’d have name collisions in the different implementations of the CC and SC interfaces.)

- Limit configuration points: Ideally all configuration can be done in one place- e.g. in the application source code or (less-ideally) in the cmake instructions.

- Assume low-latency, low-bandwidth communications: The microcontroller targets are expected to be simple, low-cost devices without ethernet or complex communication hardware. Instead, protocols like UART or maybe CAN bus are expected to be used. These will have bandwidths on the order of 1 Mbps, and will be low-latency (but lower-reliability)

Motor Controller API

The MC API can be written such that application code is expected to create MC configuration and instance structs as well as CC and SC configuration structs specific to the CC and SC chosen for the application. The configurations can be populated/modified before passing them to the MC’s initialize function which would in turn run the CC and SC initialize functions using the provided configurations. This chaining would allow (a) implementing application code using only the MC API’s initialize, start, stop, etc. functions, while (b) also enforcing a standard workflow for the CC and SC implementations. That is to say, the application code would run the MC initialize and MC start functions instead of being responsible for running the MC, CC, and SC initialize functions, and then MC, CC, and SC start functions, while also sidestepping the need to remember order of operations for using the CC and SC when implementing the application code. This would also allow implementing the MC logic in the same package defining the MC, CC, and SC interfaces.

Boundary A: Command & Data Handler (C&DH) to Motor Controller (MC):

Abstracting the boundary for a Communication Controller (CC) is fairly simple, at least in enabling a basic set of operations, like opening and closing connections and sending data:

- Configuration and Instance opaque (struct) typedefs: Similar to the strategy used in the HAL, the configuration and instance variables needed for stateful operation can be abstracted behind opaque typedefs: Forward declared in the interface package’s header files, and implemented in specific CC packages

- Open & Close: By assuming that only a single, persistent communication channel is used (a fair initial assumption for a motor connection), opening and closing connections can be aligned to controller start and stop functions. It may become necessary to introduce a restart operation, but a uC watchdog may be a simpler option assuming reasonably safe power cycling can be implemented

- Initialization: Hardware on the uC will likely need to be initialized, and so can be allocated to either an instance creation and/or initialize function call similar to what is done in the HAL

- Sending data: When sending speed actuals back to the C&DH, a

sendfunction that accepts an opaquemessagestruct can be used to allocate implementation to specific CC packages - Receiving data: The CC can use a callback to perform data reception duties and avoid the need to poll communication channels, and avoid the need to define an interface function. While this could introduce issues with interrupt storms, given that messages will be dispatched to all four (or more in the future?) wheels from a single C&DH, and low-latency but relatively low bandwidth communications channels will be used, this seems low-likelihood. Furthermore, speed control is expected to treat subsequent speed goals as independent, meaning dropped messages should have a reduced impact.

One wrinkle is the passage of data between the CC and MC. While passage of data to the SC can be done with a FIFO buffer, defining the interface between the MC and CC could create a circular dependency. If it is presumed that the CC supports functions that require actions of the SC (beyond a goal speed), then either the interfaces must introduce a function to support it, or a callback registration system needs to be in place to allow the CC to register arbitrary functions to be called from its internals. For example, to introduce an ‘Arm’ service to arm the attached ESC via a MicroROS-based CC, while the MC encapsulates the CC and SC, the CC would need a callback/vtable that can be configured in the MC’s scope to call either the MC’s ‘Arm’ function or the SC’s ‘Arm’ function. The callback/vtable approach is likely the most flexible and extensible option, but may be too error-prone without adequate testing. This also necessitates extending the SC API to support the ‘Arm’ functionality unless it can be realized via the existing interface.

Boundary D: Motor Controller (MC) to Motor Assembly (MA)

Abstracting the MC interface to the MA, that is the SC interface, can be a bit more complicated than the CC interface as the Command and Control (C2) of an encoder-driver-motor assembly tends to encompass more variability between vendors and models. Modularizing the control signal output to the driver and encoder signal input does help “eat the elephant”, but these individual interfaces still have significant amounts of variability that needs to be abstracted.

Regardless of this breadth, ultimately, the SC needs to accept data from the encoder that can be used to estimate the current motor speed, and needs to send control signals to operate the motor driver. Furthermore, if applications are expected to be customized to a particular combination of components in an MA (almost certainly different tuning parameters would be required) then using callbacks/a vtable implemented in a particular SC package would enable calling the necessary actions on, say, starting a motor given a particular control strategy, while also abstracting the control interface specific to the MA.

Take for example the goBilda Saturn and ES Motor 4260BL MAs. The goBilda ESC requires an arming operation before executing any motion instructions, whereas the 4260 does not. The application source code that configures the PID controller for the Saturn MA could define a callback that provides the required 10 cycles of PWM at 7.5% duty cycle to arm the encoder, whereas the callback for the 4260 is simply a no-op. In this way the PID controller’s logic is the same, the ESC’s ‘Arm’ callback simply becomes part of the MA-specific configuration. Similarly, the Saturn has a quadrature encoder whose ‘get actual RPM’ function would update both the current actual speed and direction based on the two channels of the encoder’s signalling, while the 4260’s single channel encoder would only update the actual speed, and either hypothesize the direction or maintain direction knowledge via another MA-specific configuration function.

This does require defining the API for the SC on a per-SC basis, meaning that when a new motor or driver type is purchased, all SCs will need to be updated to support this new hardware. Again, given that separate tuning would likely be required anyway, this seems to be an acceptable alternative to an SC interface that includes all configuration options across all combinations of control styles and MA.

Boundary C: Communication Controller (CC) to Speed Controller (SC)

For the sake of design, the MC to CC and MC to SC interfaces are discussed here in addition to the CC to SC interface. As discussed above, the MC interface can be simplified to encompass fairly straight-forward initialize, start, and stop functions. The CC and SC should also include these to support chaining, thereby relieving the application code of the need to execute all commands in triplicate.

The CC to SC interface needs to include the primary roles of each, namely accepting a goal speed and exposing actual speed for the SC, and accepting an actual speed (to be sent to the C&DH) for the CC. These can manifest as simple accessor functions. The MC managing operation of the CC and SC also introduces the need for “is ready?” functions on both the CC and SC interfaces, which also supports status reporting at the application level if desired.

Implementation & Usage

The GARP MC Interfaces (GMI) package README and doxygen API documentation have a summary of the as-implemented package interfaces and API, respectively, but some additional context related to intended usage is provided here. First refer the UML diagram below:

While the GARPCommunicationController and GARPSpeedController are shown as singular interfaces, this is to simplify presentation; That is to say, they are implemented as separate functions and are not (e.g.) collected into a single vtable.

First, functions, structures, and types are “namespaced” across the package with the garp_ prefix, followed by a subcomponent prefix mc_, cc_, or sc_ to indicate their relative scopes. For example, MC, CC, and SC configurations are contained within the garp_mc_config_t, garp_cc_config_t, and garp_sc_config_t types, respectively.

Two key stateful types are defined for each of the three scopes: the “instance” and “config” types. The config type serves as the primary means of configuring the controllers, while the instances are responsible for encapsulating their state information. Both the instance and config types are implemented as typedefs of structs, and while the MC instance and config types are both declared and defined in the GMI package (i.e. requiring no additional implementation in downstream packages or applications), the CC and SC interfaces leave these to be defined by downstream implementations. This is depicted in the UML diagram’s Motor Controller sub-scope by the enums and struct realizing (dashed open arrows) the interface types.

Application Code

For application code using existing CC and SC implementations, the first steps in a general usage pattern is to create MC, CC and SC configurations, and modify them as necessary (excerpts from the GARP ES4260 repository repository):

int main() {

...

tq = hal_create_queue(sizeof(float), 4u);

aq = hal_create_queue(sizeof(float), 4u);

...

SC_CONFIG = garp_sc_create_config();

SC_CONFIG->counts_per_rev = 1993.6;

SC_CONFIG->kp = 0.75f;

...

SC_CONFIG->target_queue = tq;

SC_CONFIG->actual_queue = aq;

...

CC_CONFIG = garp_cc_create_config();

CC_CONFIG->node_name = "cc_node_name";

CC_CONFIG->node_namespace = "mobility";

...

CC_CONFIG->target_rpm = tq;

CC_CONFIG->actual_rpm = aq;

garp_mc_config_t MC_CONFIG = {

.name = "ES 4260BL PID+uROS",

...

.update_period_ms = 45

};

Note that two queues were made previously to support passing data between the controllers. This is done to allow access to the queues in the application, MC, CC, and SC scopes without needing to explicitly define a queue interface as part of the MC interface.

Once the configurations are in place, the MC instance can be created which will internally create the CC and SC instances. These will then be available via the cc_inst and sc_inst fields of the mc_instance_t struct. (Note here that the typedef is used simply to remove the need to type the struct keyword, at the risk of obfuscating struct operations, which is typically alleviated by modern IDEs.)

garp_mc_instance_t* mc_inst = garp_mc_create_instance(&MC_CONFIG, CC_CONFIG, SC_CONFIG);

The MC instance can then be used to initialize and start the controller group. The MC’s start function does not necessarily need to return if, for example, the CC should execute an infinite loop. The same holds for the SC, as the HAL’s hal_start_thread method is used to allow the SC to operate independently of the CC. Note however, that the speed controller must report that it is ready (via a call to garp_sc_ready() before the CC will be started. In the future, this may be parameterized in the MC configuration such that either the CC or SC can be started first, and waiting for one to be ready before starting the other can be configured.

garp_mc_result_t res;

res = garp_mc_init(mc_inst);

res = garp_mc_start(mc_inst);

Communication Controller Implementation

Creating a communication controller requires implementing the interface defined in garp_cc_interface.h. This requires definition of the following items (see the doxygen API documentation for full signatures):

struct garp_cc_configandstruct garp_cc_instance: CC configuration and stateful CC instancestructs to allow abstraction of configuration parameters and internal CC state across implementations. Thesestructsaretypedef‘d to their_topaque aliases in the GMI static library at link time.struct garp_cc_message: Message structure opaque typedef to allow abstraction across implementations; Used by thegarp_cc_sendfunction. This struct is alsotypedef‘d togarp_cc_message_t.garp_cc_create_config(): Responsible for creating a new configurationstructgarp_cc_destroy_config(): Destroys a configurationstruct, typicallyfreeing it. If the application’s primary method of error handling is a reset, this may be unnecessary.garp_cc_create_instance(): Creates a new instancestructfrom a configuration; Typically responsible for allocating any required heap memory used by the CCgarp_cc_destroy_instance(): Destroys an instance including deallocating memorygarp_cc_init(): Initializes the CC; Typically initializes hardware and can set initial values for internal CC state; Can also configure timers and interruptsgarp_cc_start(): Finishes setting initial internal CC state and enables interrupts and timersgarp_cc_stop(): Stops CC operations and disables interrupts and timersgarp_cc_send(): Sends message via CC; Typically used to send motor speed actuals or other information as specified in thegarp_cc_messagestructgarp_cc_ready(): Returns if a CC is ready for operation

As an example, consider the MicroXRCE communication channel used in the GARP MC uROS implementation. The instance implementation looks like the following:

struct garp_cc_instance {

garp_cc_config_t* config; //!< GARP CC Configuration

rcl_allocator_t* allocator; //!< uROS allocator

rclc_support_t* support; //!< uROS support

rclc_executor_t* executor; //!< uROS executor

rcl_node_t* node; //!< uROS node

rcl_publisher_t* actual_pubx; //!< uROS actual RPM publisher

rcl_subscription_t* target_subx; //!< @brief uROS target RPM subscription

std_msgs__msg__Float32* msg_buffer; //!< @brief uROS incoming message buffer

rcl_service_t* arm_service; //!< uROS arming service

std_srvs__srv__Trigger_Request* arm_req_buffer; //! @brief uROS arming service request buffer

std_srvs__srv__Trigger_Response* arm_resp_buffer; //! @brief uROS arming service response buffer

hal_atomic_t* running; //!< If controller has been started

hal_uart_instance_t* uart_inst; //!< UART instance

garp_cc_cb_vtable_entry_t callbacks[GARP_CC_EVENT_COUNT]; //! @brief Event callbacks vtable

};

Here, the instance fields are defined, including a pointer to the CC configuration as well as several MicroROS ROS Client Library (RCL) components and a callback vtable; This becomes a state encapsulation that is passed to GARP CC functions. Also consider the implementation of the garp_cc_send function:

typedef std_msgs__msg__Float32 garp_cc_message;

...

garp_cc_result_t garp_cc_send(garp_cc_instance_t* instance,

const garp_cc_message_t* msg) {

if (!instance) {

LOG_ERROR("uROS: Invalid/null instance provided");

return HAL_INVALID_ARG;

};

if (!msg) {

LOG_ERROR("uROS: Invalid/null data provided");

return HAL_INVALID_ARG;

};

rcl_ret_t rc = rcl_publish(instance->actual_pubx, msg, NULL);

if (rc != RCL_RET_OK) {

LOG_WARNING("Failure while sending message");

};

return HAL_OK;

};

After checking inputs, the function sends a message over the communication channel using the rcl_publish function and a pointer to the actual RPM publisher stored in the instance. This is simplified by the aliasing of the MicroROS std_msgs__msg__Float32 type to garp_cc_message (which is aliased in the GMI package to garp_cc_message_t). If the message structure were more complex, additional handling could be done using the fields defined in the garp_cc_message struct to produce a message in the format needed by rcl_publish.

Speed Controller Implementation

Similar to the CC, creating a speed controller requires implementing the interface defined in garp_sc_interface.h. The components of the interface to defined are (see the doxygen API documentation for full signatures):

struct garp_sc_configandstruct garp_sc_instance: SC configuration and stateful SC instancestructs to allow abstraction of configuration parameters and internal SC state across implementations. These structs aretypedef‘d to their_topaque aliases in the GMI static library at link time.garp_sc_create_config(): Responsible for creating a new configurationstructgarp_sc_destroy_config(): Destroys a configurationstruct; Typically called by the application logic to create a configurationstructwhich is manipulated by the application logic, and then supplied togarp_sc_create_instance()garp_sc_create_instance(): Creates a new stateful instancestructfrom a configuration; Typically responsible for allocating any required heap memorygarp_sc_destroy_instance(): Destroys an instance including deallocating memorygarp_sc_init(): Initializes the SC; Typically initializes hardware and can set initial values for internal SC state; Can also configure timers and interruptsgarp_sc_start(): Finishes setting initial internal SC state and enables interrupts and timersgarp_sc_stop(): Stops SC operations and disables interrupts and timers ‘garp_sc_set_target(),garp_sc_get_target(): Accesses target motor speed in RPM ‘garp_sc_get_actual(): Get current actual (estimated) motor speed ‘garp_sc_arm(),garp_sc_disarm(): Arms or disarms the SC, typically via an attached ESCgarp_sc_ready(): Returns if an SC is ready for operationgarp_sc_armed(): Returns if an SC has been armed; This may reflect if the SC is armed, depending on implementation and hardware

As an example, consider the implementation of a PID speed controller in the GARP MC PID repository. The configuration interface (which is specific to the PID controller) is implemented in a header file that is included by application code to expose the fields of the garp_sc_config_t struct.

struct garp_sc_config {

/*! @brief Timeout in milliseconds to wait for the motor to stop

@note This value must be non-zero

*/

uint32_t stop_timeout_ms;

//! @brief Threshold in RPM under which the motor is considered stopped

float stopped_threshold_rpm;

/*! @brief Number of encoder counts per revolution

@note This value must be greater than zero

*/

float counts_per_rev;

/*! @brief Proportional gain for the PID controller in SU

@note This value is *typically* greater than zero

*/

float kp;

/*! @brief Integral gain for the PID controller in SU

@note This value is *typically* positive

*/

float ki;

/*! @brief Derivative gain for the PID controller in SU

@note This value is *typically* positive

*/

float kd;

/*! @brief Desired PID loop period in us

@note Setting the period to 0 will set the PID loop to free-running

*/

uint64_t loop_period_us;

//! @brief Maximum RPM for motor

float max_rpm;

//! @brief Target speed queue in RPM

hal_queue_t* target_rpm;

//! @brief Actual speed queue in RPM

hal_queue_t* actual_rpm;

/*! @brief Period in milliseconds at which to share actual speed

@note Value must be greater than zero

*/

uint32_t actual_update_period_ms;

/*! @brief ESC drive function

@param rpm Desired RPM

@returns void

This function accepts normalized PID effort in [-1.0, +1.0] and drives

the ESC via the appropriate signaling. This could include compensating

for a control deadzone, clipping output at a maximal level, setting a

PWM output duty cycle, and/or setting a direction pin value.

*/

garp_sc_direct_esc_fxn_t direct_esc_fxn;

/*! @brief ESC initialization procedure

@param input Normalized level of effort in [-1.0, +1.0]

@returns void

This function is called to initialize the ESC connection as part of the

PID controller. This could include initializing PWM output.

*/

garp_sc_procedure_t init_esc_fxn;

/*! @brief ESC Start procedure

This function is called to start the ESC as part of the PID controller.

This could include triggering a self-check of the ESC.

*/

garp_sc_procedure_t start_esc_fxn;

/*! @brief ESC Arm procedure

This function is called to arm the ESC as part of the PID controller.

This could include providing a given PWM duty cycle for a given period

of time.

*/

garp_sc_procedure_t arm_esc_fxn;

/*! @brief Update actual speed

@returns Actual motor speed in RPM

This function is called by the PID controller to get an updated actual

speed of the motor from the encoder hardware.

*/

garp_sc_enc_feedback_fxn_t get_actual_rpm_fxn;

/*! @brief Encoder initialization procedure

This function is called to initialize the encoder hardware as part of

the PID controller. This could include registering encoder input pins

and setting pull up/down configuration.

*/

garp_sc_procedure_t init_enc_fxn;

/*! @brief Encoder start procedure

This function is called to start the encoder as part of the PID

controller. This could include enabling interrupts on the encoder input

pin(s).

*/

garp_sc_procedure_t start_enc_fxn;

};

Here typedefs defining virtual function signatures are used to provide callbacks to encoder and esc functionality. In the future these interfaces may be moved into the base MC Interfaces package to avoid having to repeat these entries in the configuration struct across multiple SC implementations, but this is pending additional SC implementations and motor hardware integrations to determine if this design is adequate and optimal. Similar to the CC example, consider the implementation of the garp_sc_init function:

// From ES4260 package

void init_esc_fxn(void) {

// Initialize PWM to drive ESC

esc_pwm_config = hal_create_pwm_config();

hal_configure_pwm(esc_pwm_config, PWM_PIN, 20e3f, 10001);

// Initialize direction pin

hal_init_gpio(DIR_PIN, HAL_GPIO_OUT);

LOG_DEBUG("Esc: ESC initialized");

};

void init_enc_fxn(void) {

counts_ = hal_create_atomic(1);

if (!counts_) {

LOG_FATAL("Failure while creating encoder counts atomic");

return;

};

// Last encoder time

last_tick_us_ = hal_create_atomic(8);

if (!last_tick_us_) {

LOG_FATAL("Failure while creating encoder last tick atomic");

return;

};

// Initialize encoder input pins' gpio

hal_init_gpio(ENC_PIN, HAL_GPIO_IN);

// Attach interrupt (but don't enable until starting encoder)

hal_attach_interrupt(ENC_PIN,

HAL_IRQ_EDGE_RISE || HAL_IRQ_EDGE_FALL,

&enc_tick_isr_,

false);

LOG_DEBUG("Enc: Encoder initialized");

};

// From GARP SC PID Controller package

garp_sc_result_t garp_sc_init(garp_sc_instance_t* instance) {

if (!instance) {

LOG_ERROR("PID: Invalid/NULL instance provided");

return GARP_SC_RESULT_INVALID_PARAMETER;

};

if (!instance->config) {

LOG_ERROR("PID: Unconfigured instance provided");

return GARP_SC_RESULT_INVALID_PARAMETER;

};

if (instance->config->init_esc_fxn) {

instance->config->init_esc_fxn();

};

if (instance->config->init_enc_fxn) {

instance->config->init_enc_fxn();

};

return GARP_SC_RESULT_OK;

};

Here the PID controller defined in the GARP MC PID Controller package calls the init_enc_fxn and init_esc_fxn functions defined in the (motor hardware-specific) ES4260 package. The init_ functions use the HAL to initialize the GPIO and PWM hardware needed to receive interrupts and provide a PWM control signal to the motor assembly, respectively. The PID controller sets these virtual function fields in the configuration struct to NULL when creating it, such that the PID controller can check for their specification before calling them. For a motor that does not need to initialize any hardware these functions could be set to no-ops or just never initialized. Alternate SCs could implement this differently as this aspect of the interface is not defined as part of the GMI package.

Summary

To simplify development and improve maintainability within the GARP robotics platform, this article introduces a modular motor controller interface composed of three well-defined components: the Communication Controller (CC), Speed Controller (SC), and Motor Controller (MC). The architecture emphasizes clear boundaries to promote portability, testability, and reuse across embedded targets and surrounding systems. It currently supports velocity control, with future extensions to position and torque control modes anticipated. Concrete implementation guidance and examples are included to help developers adopt the interface without needing major refactoring as capabilities evolve.